Although the discoveries of Newton respecting the Inflection of Light were first published in his Optics in 1704, yet there is reason to think that they were made at a much earlier period. Sir Isaac, indeed, informs us, in his preface to that great work, that the third book, which contains these discoveries, “was put together out of scattered papers;” and he adds at the end of his observations, that “he designed to repeat most of them with more care and exactness, and to make some new ones for determining the manner how the rays of light are bent in their passage by bodies, for making the fringes of colours with the dark lines between them. But I was then interrupted, and cannot now think of taking these things into consideration.” On the 18th March, 1674, Dr. Hooke had read a valuable memoir on the phenomena of diffraction; and, as Sir Isaac makes no allusion whatever to this work, it is the more probable that his “scattered papers” had been written previous to the communication of Dr. Hooke’s experiments.

The phenomena of the inflection of light were first discovered by Francis Maria Grimaldi, a learned Jesuit, who has described them in a posthumous work published in 1665, two years after his death.29

Having admitted a beam of the sun’s light through99 a small pin-hole in a piece of lead or card into a dark chamber, he found that the light diverged from this aperture in the form of a cone, and that the shadows of all bodies placed in this light were not only larger than might have been expected, but were surrounded with three coloured fringes, the nearest being the widest, and the most remote the narrowest. In strong light he discovered analogous fringes within the shadows of bodies, which increased in number with the breadth of the body, and became more distinct when the shadow was received obliquely and at a greater distance. When two small apertures or pin-holes were placed so near each other that the cones of light formed by each of them intersected one another, Grimaldi observed, that a spot common to the circumference of each, or, which is the same thing, illuminated by rays from each cone, was darker than the same spot when illuminated by either of the cones separately; and he announces this remarkable fact in the following paradoxical proposition, “that a body actually illuminated may become more dark by adding a light to that which it already receives.”

Without knowing what had been done by the Italian philosopher, our countryman, Dr. Robert Hooke, had been diligently occupied with the same subject. In 1672, he communicated his first observations to the Royal Society, and he then spoke of his paper as “containing the discovery of a new property of light not mentioned by any optical writers before him.” In his paper of 1674, already mentioned, and which is no doubt the one to which he alludes, he has not only described the leading phenomena of the inflection, or the deflection of light, as he calls it, but he has distinctly announced the doctrine of interference, which has performed so great a part in the subsequent history of optics.30

100 Such was the state of the subject when Newton directed to it his powers of acute and accurate observation. His attention was turned only to the enlargement of the shadow, and to the three fringes which surrounded it; and he begins his observations by ascribing the discovery of these facts to Grimaldi. After taking exact measures of the diameter of the shadow of a human hair, and of the breadth of the fringes at different distances behind it, he discovered the remarkable fact that these diameters and breadths were not proportional to the distances from the hair at which they were measured. In order to explain these phenomena, Newton supposed that the rays which passed by the edge of the hair are deflected or turned aside from it, as if by a repulsive force, the nearest rays suffering the greatest, and those more remote a less degree of deflection.

Thus, if X, fig. 10, represents a section of the hair, and AB, CD, EF, GH, &c. rays passing at different distances from X, the ray AB will be more deflected than CD, and will cross it at m, the ray CD will for the same reason cross EF at n, and EF will cross GH at o. Hence the curve or caustic formed by the intersections m, n, o, &c. will be convex outward, its curvature diminishing as it recedes from the vertex. As none of the passing light can possibly enter within this curve, it will form the boundary of the shadow of X.

The explanation given by Sir Isaac of the coloured fringes is less precise, and can be inferred only from the two following queries.

1. “Do not the rays which differ in refrangibility differ also in flexibility, and are they not, by these different inflections separated from one another, so as after separation to make the colours in the three fringes above described? And after what manner are they inflected to make those fringes?

2. “Are not the rays of light in passing by the edges and sides of bodies bent several times backwards and forwards with a motion like that of an eel? And do not the three fringes of light above mentioned arise from three such bendings?”

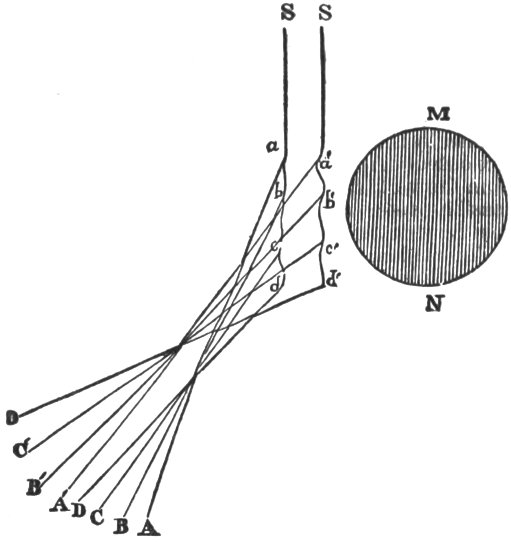

The idea thus indistinctly thrown out in the preceding queries has been ingeniously interpreted by Mr. Herschel in the manner represented in fig. 11, where SS are two rays passing by the edge of the body MN. These rays are supposed to undergo several bendings, as at a, b, c, and the particles of light are thrown off at one or other of the points of contrary flexure, according to the state of their fits or other circumstances. Those that are thrown outwards in the direction aA, bB, cC, dD, will produce as many caustics by their intersections as there are deflected rays; and each caustic, when received on a screen at a distance, will depict on it the brightest part or maximum of a fringe.

In this unsatisfactory state was the subject of the inflection of light left by Sir Isaac. His inquiries were interrupted, and never again renewed; and though he himself found that the phenomena were the same, “whether the hair was encompassed with air or............