Yet numerous specimens do exist, including drinking glasses of all shapes and sizes, as well as fruit dishes, epergnes, sweetmeat glasses, decanters, and salt-cellars, which are undoubtedly Irish in their origin, and which are generally known as “Waterford” glass.

As far as can be determined, glass-making in various forms, enamelling, and even mosaic work and cameos, were carried on in Ireland as early as the beginning of the eighth century.

The finest examples of the earliest period are to be found in the Royal Irish Antiquities{129}

FIG. 29.—NAILSEA JUG AND MUG.

Collection, which includes the famous Ardagh Chalice, the Tara Brooch, the Cross of Cong, and the Crozier of Clonmacnoise, as well as other well-known and interesting exhibits. At any rate, experts are agreed that even at this early date the art of enamelling on glass was practised in Ireland, being probably introduced by the Ph?nicians who, in turn, had acquired the art from Ancient Egypt. In support of this belief is the fact that a large piece of red enamelled glass was found in the Rath of Caílchon on Tara Hill; but it is equally clear that the art of glass-making, if introduced at the time mentioned, speedily fell into desuetude, for there is no mention of any manufacture of glass between the ninth and the seventeenth centuries, nor are there to be found any specimens which may be attributed to this period. There are, further, no traces of the manufacture even of window glass of the commonest description.

In the seventeenth century, however, there were many interesting squabbles with regard to glass-making patents and their infringement, and there are records of petitions to the King concerning them; but from the Patent Roll of King James I. it appears that little was done.{130} Still, we have it on record that permission was given to import glass in 1675, and it is suggested that craftsmen in Ireland attempted to imitate the work of Continental glass-workers, and various sums of money were granted by the Universities and others interested, to assist them in so doing. Some progress undoubtedly was made, for it is clear that by the eighteenth century factories were in existence and glass was being actually made in Dublin, Waterford, Cork, Belfast, and Londonderry.

Some examples of early Waterford glass are, as far as shape and size go, replicas of glasses made in England at about the same period, but the reason for the almost immediate popularity of the Irish glass was its perfection of colour. A fine specimen which recently came under my notice is a preserve jar with cover (Fig. 30), about 18 inches in height, handsomely cut and shaped, with a square base and a fine spiked cover. It is undoubtedly one of the finest examples of early Waterford glass which it has been my privilege to inspect.

Genuine Waterford glass is characterised by a peculiar bluish tint in its body—due, it is generally recognised, to the presence of lead—but

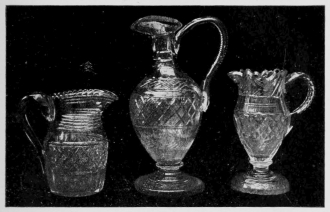

OLD WATERFORD GLASS WATER JUGS. 18th-19th CENTURY.

FIG. 30.

attributed by some to some peculiar quality of the flint employed, which was obtained from pits in the vicinity. Personally, I lean to the former hypothesis. Cork glass, on the other hand, is distinguishable by a pale yellow or amber tint—in all probability the result of the presence of iron. These tones are characteristic, for though the colouring of glass has been brought by modern workers to a fine art, yet no one has succeeded in exactly reproducing them so that, to the expert eye, the genuine old Irish glass is unmistakable.

About the year 1753 the Dublin Society offered a premium for the establishment of a glass factory in County Cork. There seems, however, to have been some reluctance in taking advantage of the offer, for it was not until 1782 that the first glass factory was established there. Then Atwell Hayes, Thomas Burnett and Francis Richard Rowe demanded assistance from Parliament in carrying on the industry. They proposed to erect two houses, one for bottles and one for window glass and, from their advertisements appearing shortly after in the Irish papers, offering to sell glass at their manufactory, and guaranteeing satisfaction, it would appear{132} that their venture met with considerable success.

From 1780 onward Cork exported a good deal of glass. In the year 1801 alone, the considerable number of 111,000 drinking glasses was sent to America, Portugal, and various other places abroad, while in the next year there is record of 6129 dozen bottles and 40,000 drinking glasses being shipped abroad, which indicates a considerable output.

The trouble involved in founding such an industry in those days must have been considerable. In this case, two years were taken up in procuring the necessary concessions, but the industry, once started, took firm root, and the advertisements appearing in the Press—in particular, The Hibernian Chronicle (May 1784) and The Cork New Evening Post (1792), copies of which are preserved in the Museum of Dublin Antiquities, indicate what progress it was making and, incidentally, possess a curious interest from their quaint wording and setting forth.

The following is an example:—

“With choicest glass from Waterford,

Decanters, Rummers, Draws, and Masons,

Flutes, Hob-nobs, Crofts, and Finger Basins,

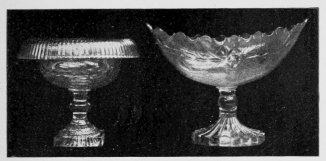

OLD WATERFORD BOWLS. 18th-19th CENTURY.

OLD ENGLISH AND IRISH CELERY BOWLS.

FIG. 31.

Proof Bottles, Goblets, Cans, and Wines,

Punch Juggs, Liqueurs, and Gardevins,

Salts, Mustards, Salads, Butter keelers,

And all that’s sold by other dealers.

Engraved or cut in newest taste,

Or plain—whichever pleases best.

Lustres repaired or Polished bright,

And broken glasses matched at sight.

Hall globes of every size and shape,

Or old ones hung and mounted cheap.”

In style, as we have already said, Waterford glass closely approximates to Old English of the Georgian period. If anything, however, the cutting was deeper, the angles and spikes being often so sharp as to make it dangerous to grasp the pieces tightly.

Numerous table services of glass of this period exist, as well as decanters, punch bowls, and dishes. All are deeply cut, the chief designs being the hobnail and diamond patterns. Sometimes we find fluted stems and finely cut spiked or striped sides. The majority of the larger pieces, such as the punch and salad bowls, had square feet or bases which, while possibly adding to their stability, certainly enhanced the beauty of their appearance. The salad bowl shown on the left of Fig. 31 is an excellent example: the{134} collar or turn-over at the rim is remarkable for its depth and also for its superb cutting. The bowl on the right is a remarkable specimen of very uncommon type. It is oval in shape—a shape not easily blown even at the present time—and has facet cutting upon the outside as well as a particularly fine cut scalloped edging. The base, too, is in admirable keeping with the rest of the design.

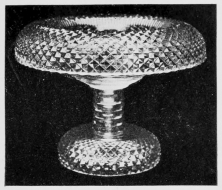

Fig. 32 is another particularly fine piece of Waterford glass, worthy of note as an example of hobnail cutting, as well as for the depth of its collar and its general effectiveness.

The celery bowls shown in Fig. 31 are also admirable specimens. That on the left is waisted and is “strawberry” cut. The centre one is an example of fine fluted and diamond cutting, with a square base and domed foot, and the one on the right has a collar and is flat cut on the middle of the bowl.

Oval or oblong dishes for fruit or sweetmeats were often made with fan-shaped rims and sides, high in the centre, then sloping downwards, to rise again to an equal height at the ends. Old Irish cut-glass salt-cellars are greatly sought after nowadays for the dinner-table, and have,

OLD WATERFORD CENTREPIECE, WITH A DOUBLE COLLAR AND DOME FOOT.

A PAIR OF OLD WATERFORD PRESERVE JARS, COVERS AND STANDS.

FIG. 32.

with collectors, almost completely ousted the old Georgian silver “salts.” They were often exquisite in design and shape, some being miniature models of the large punch bowls or sweetmeat glasses. The illustration (Fig. 14) is of an imitation pair in Old Sheffield stands.

The water jugs also are of exceptional interest. They were usually shaped on a fine and graceful model, and are heavily cut into step or deep-ringed incisions generally with massive ornamentations of leaves or panel cuttings round the neck, and diamond cuttings and flat fluting at the base. So eager, indeed, were certain of the designers to ensure that no part of the jug should be without its ornamentation, that they went so far as to adorn the handles with deep cutting inside, and placed a huge, deeply cut star on the outside bottom. Weighty substance and wealth of ornament are thus characteristic of Waterford glass, although it is, of course, impossible to say that all Irish glass displaying these qualities came from the Waterford houses.

The jugs illustrated in Fig. 30 are among the finest specimens in existence, and are from the Dublin Museum Collection. A careful inspection will reveal most of the characteristics{136} to which we have referred. The figure on the left is the type most familiar nowadays; the neck is step cut, the body is “strawberry,” and the base is flat fluted. The centre piece is a jug of the earliest shape, and is curiously cut. A band of strawberry cutting round the widest part of the body is flanked top and bottom by bands of leaf cutting; the lip seems so disproportionately large as to give the piece an almost top-heavy appearance. The handle, too, is abnormally large, and is incised on the inside. Its interest is rather more historical than artistic. The third, on the right, is a fine example of flat cutting, the rim being scalloped and the handle deeply scored with “niches,” besides being lavishly ornamented. The base is curious in that it is domed—a very unusual form for a jug.

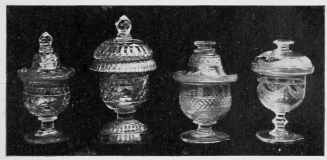

Many of the Waterford pieces, especially the preserve jars with turn-over collars, were made with covers to protect the upper rim. These are very attractive pieces, and are found in all shapes and sizes. The smaller ones, both with and without collars, are exceedingly pretty and not difficult to acquire.

The four shown in Fig. 33 give an excellent idea of what to expect. Each is distinct, both{137}

IRISH BOWLS.

SPECIMENS OF IRISH PRESERVE JARS AND COVERS. 18th-19th CENTURY.

FIG. 33.

as regards design and ornamentation. It will be interesting for the reader to compare them and discover the characteristic features of each.

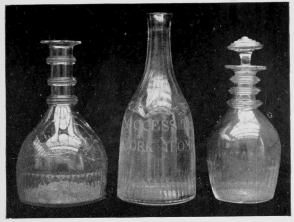

The decanters which came into vogue in the eighteenth century display the same general character and are very similar in type to the English decanters of the same date. Three of them are shown in Fig. 34, and it may be of service to compare them with the four shown in Fig. 14. The stopper of the central one is of the button type, those of the other two being of the more common “mushroom” variety.

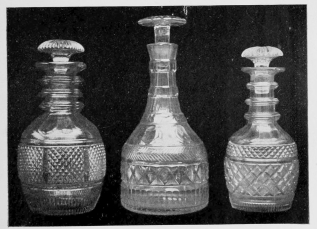

The beautiful pair shown in Fig. 35 deserve a word of special mention. One feature is the lavish use of step cutting round the neck and shoulders, and another the strawberry empanelment on the body. The fine diamond cutting and fluting of the stoppers are also worthy of notice.

Drinking glasses, as we have said, were produced in large numbers. They are generally of two types, the one barrel or bowl shaped after the fashion of our English rummers, the other straight-sided glasses on stems. The specimens shown in Fig. 12 give some idea of their general style as well as of the variety of ornament employed.{138}

It may be well to point out here, for the benefit of those who desire to acquire specimens of Waterford glass, some of the many differences which may be detected between the genuine article and its modern imitation.

To begin with a simple example—the prettily shaped wine glasses of the period with air-threaded or twisted stems are generally reproduced accurately enough, but the twist or thread in the old glass has a pronounced milky appearance as compared with the dead white of the modern reproduction. The twist also is not so regular and even, and the feet are larger and apparently slightly clumsier in the authentic specimens. Numerous connoisseurs attach importance to the centre of the foot, which is usually rough and uneven in the old glass. Another test frequently relied upon by collectors is the fact of the foot being turned over—a fashion which, it is said, was followed only with the earliest specimens. While, however, this may provide corroborative evidence, I should be sorry to rely upon it as a sole test.

Probably the best criterion of all is the colour. It has, as I have already noted, a dull bluish tinge readily recognisable when the specimen is

OLD CORK GLASS DECANTERS (EARLY 18th CENTURY).

OLD WATERFORD DECANTERS (18th—19th CENTURY).

FIG. 34.

held up to the light. The better kinds, too, have almost invariably a large and deep-cut star on the bottom.

Cork glass is rarer than Waterford—a result due to the fact that the Cork factories were in existence only for a comparatively short time. The pieces, too, are slighter, less heavy, and by no means so deeply cut. It is much frailer in appearance and, at the first glance, less attractive; but its great beauty is a charming delicacy both of colour and form which grows upon one’s taste. The wine glasses in particular would at once appeal to a connoisseur from this point of view alone. The three decanters shown in Fig. 34 need only be compared with the Waterford decanters shown elsewhere for the lack of heavy cutting to be immediately noticed. The centre one is interesting as being a commemoration piece probably made in the year when the Cork Yeomanry was formed.

Irish glass was not unfrequently profusely engraved and gilt. The gilding was done during manufacture, the gold being burnt in by the aid of borax. In existing specimens much of the gilding has been worn off, so that only traces remain. In cases where it has disappeared{140} entirely a careful scrutiny will show pits and roughnesses, indicating where the decoration formerly stood. Sometimes the places can even be discerned by the touch. Dutch, German, and Austrian reproductions have from time to time flooded the market to be sold to the unwary collector as veritable specimens of Irish art. But these on examination are found to be, as a rule, so coarse and unfinished in their execution that the fraud is obvious. The gilding, in particular, is far inferior to the work of the old craftsmen, who were guided solely by the artist’s desire for perfection, irrespective of toil or cost.

Now and again specimens of Irish moulded glass crop up. These are chiefly pint and half-pint beer glasses with fluted sides and somewhat sparse engraving. The moulded glass is, of course, easily detected since the edges of the fluting are rounded and blunt. The pieces themselves are usually absurdly light if intended for Cork glass, or clumsily heavy if they are intended to pass for the Waterford variety.

A large field, therefore, opens to the average collector of Irish glass. It is wonderfully fine and not too difficult to obtain. Many collectors

18th CENTURY CUT GLASS WATERFORD DECANTERS.

18th CENTURY FINGER BOWL.

FIG. 35.

too, in their desire to acquire only the earliest specimens, overlook the cut glass altogether as too modern. In spite of this Irish cut glass is now more valuable and far more sought after than any other. After exhaustive inquiries I am satisfied that in Ireland, England, France, and the United States specimens of genuine Irish glass are still to be found, often in the most unlikely places—the property of persons who could not be expected to know their value and of others who ought to but do not.

A little personal experience may be worth repeating here. I was in a small, dilapidated general shop near the London Docks; the shopkeeper, fancying he detected in me a possible victim, drew my attention to a pair of celery glasses and began to descant upon their age, the difference between them and Cork or Bristol glass, and so on. After I had examined them carefully and satisfied myself that they were genuine—they were about 10 in. high with a very thin herring-bone cutting upon their flat-cut sides—I asked the price, which was absurdly high; then, disclosing my identity, I asked what he would say if I told him they were not genuine but only reproductions. To my utter astonishment,{142} he exclaimed that he “must have been done.” The price—“if they were any use to me”—dropped considerably. Then I told him they were genuine, and sent a friend of mine, who is a collector, to purchase them, but not without the man endeavouring to obtain a price which was not only far above what he had asked me but considerably above the real value of the articles.

I record this episode for the benefit of my readers who may be tempted to depend upon the seller’s opinion for a guarantee of the genuineness of their “finds.” Speaking generally, the ordinary shopkeeper’s knowledge is of the most superficial type and should never be relied upon, while, of course, his interest lies entirely in one direction.

Research fails to throw much light upon the glass factory of Londonderry, nor is it easy to find pieces bearing indisputable proof of their origin. But it is a fact that in 1820 one John Moore transformed a sugar establishment in that city into a glass factory and, with his son, carried on the manufacture until 1825. Then a prohibitive duty stopped it. It is possible that only the black ale bottles were manufactured there. As for the glass exported from Londonderry to{143} America, it is difficult to determine whether it was manufactured in that city or merely exported thence. The latter is the more probable, since by the Act of 1746 a duty of 9s. 4d. was imposed on every cwt. of material used in making Crown plate, flint, and white glass in Ireland, as against a duty of 2s. 4d. per cwt. in England, from which it will appear that Ireland in those days had no great incentive to manufacture glass in opposition to England.

It is almost impossible to obtain authentic examples of the work of individual Irish factories. Nor can one state with any degree of certainty that a certain pattern, cutting, or style is identified with any one factory or another. Both the Waterford and Cork glass firms came from England, and brought with them English workmen. Hence it is pretty certain that the designs and styles adopted by them were replicas of those utilised in England, and not peculiar to Ireland or copies of ancient Irish relics. So, too, with the ornamentation.

Possibly some of the earliest Waterford glass was gilt, for in 1784 one John Grohl obtained a concession for this purpose. A native of Saxony, he probably brought with him the secret of his{144} art, for the “disclosure” of which he and a certain John Hand were rewarded by the Dublin Society. The finest diamond cutting, strawberry cutting, and flat fluting were done at Waterford; but pieces were not always cut at their place of manufacture. Thus we hear of a Waterford dish going to Cork for ornamentation with the characteristic designs of the factories there. The cutters, too, had often to decorate their pieces to the purchaser’s taste.

There seems to have been little coloured glass made in Ireland, although specimens are not unfrequently offered for sale. The writer was offered recently, on the Continent, some “Old Irish glass” of perfect colouring—deep blue, red, and yellow, with fine heavy cutting—but the lightness of the pieces proved them modern, probably from some Dutch factory.

In concluding this chapter a word may be given to Scottish glass, which is very like Irish in texture, although its existence is commonly ignored by collectors and writers alike. As an industry glass-making was, of course, of little importance in Scotland, but it is interesting to learn that in the reign of James VI., John Maria{145} dell’ Aqua of Venice was appointed Master of the Glass-Works in Scotland. The famous liqueur glass shaped like the flower of the thistle was probably from a Bohemian original. It is heavily cut, with an acorn bottom upon a round stem, and reproductions can be seen in almost every shop window that displays glass. Early examples are difficult to obtain and their genuineness equally difficult to guarantee. It is assumed that many of the Jacobite glasses were manufactured in the Scottish factories. Secrecy being absolutely essential, it is hardly necessary to state that no authentic records of production are to be found.

The courtesy of the authorities of the Dublin Museum has enabled me to add another, and, from a collector’s point of view, a most interesting, section on the subject of Irish glass.

The museum possesses one of the finest collections of Old Irish glass in existence, many pieces from which are reproduced in the illustrations to this chapter. These illustrations are of pieces as nearly perfect as it is possible to obtain, and are therefore useful in enabling the collector to form a standard as regards this particular form of glass.

The three decanters illustrated in Fig. 34 are{146} undoubtedly Cork glass. Apart from the fact that the centre one bears an inscription, “Success to Cork Yeomen,” which seems to indicate that it was made about the time the Irish Brigade was being raised—early in the nineteenth century—it bears all the distinctive characteristics of the Cork factories.

The drinking glasses (Fig. 12) are also undoubtedly Irish, of about the same period, and probably came from Waterford. The reader should carefully note the cutting of the two end pieces; they are of totally different types, each being perfect in its own style. That on the left has the hobnail cutting common in England about the time when the Irish factories were first established. It was probably imitated from an English model or made by one of the English craftsmen who were largely responsible for the introduction of glass manufacture into Ireland.

The end glass on the right-hand side is an excellent example of the grace, beauty, and simplicity associated with the best Waterford pieces; its flat-cut sides are characteristic of its place of origin. I have occasionally seen similar specimens in London, and they have always appealed to me as the most perfect examples of{147} the Irish drinking glass of the eighteenth century. The other two specimens are of the same type as the English rummers or punch glasses; they are prettily engraved, and make an effective contrast to the other glasses of the same period.

Irish cut-glass decanters and stoppers, such as the specimens illustrated in Fig. 34, are not difficult to find nowadays if one is expert enough and careful enough to avoid the many imitations that exist. High prices are demanded for genuine pieces in which the cutting and colour are good, and which satisfy the tests by which the connoisseur judges the antiquity of his finds.

The centre decanter has a finger-fluted base, and the length of the neck makes it an unusual specimen. Possibly the idea was to enable it to be more easily grasped and held when full; but the design is undoubtedly graceful, and this is one point which the amateur collector should never ignore when seeking to make a worthy collection. It is well to bear in mind both artistic merit and intrinsic worth.

Two other fine early specimens of Waterford glass are illustrated in Fig. 31. The “collared” or turn-over flower bowl is a fine example{148} of eighteenth-century work. The cutting, it will be seen, is entirely different from that of the piece on the right; for whereas the latter is entirely flat cut, with the exception of its finely scalloped edges in the former, the whole design is finished in the “fluted” style. In both, as in most pieces of the kind and period, the “dome” or hollow foot is found.

The large glass dish on a stand on the other side is almost unique. Such pieces are very difficult to find in their entirety; indeed, the only other existing, to my knowledge, is in the Marquis of Bute’s collection. Perfect specimens are hardly obtainable now except when a fine collection is dispersed at the death of its owner. Even then, as all such notable pieces are well known to collectors, the competition for them is very keen, and the private buyer, unless his purse is of the “bottomless” kind, is hardly likely to obtain them. Occasionally one may, by happy accident, come across a really fine piece in some unexpected quarter, but such chances are few and far between. Moreover, there is always between the finder and his find the spectre of the fake merchant, whose wont it is to plant his most seductive wares in out-of-the-way{149} places, so as to give them a fictitious appearance of genuineness. No important piece should ever be purchased without an inquiry into its history. It ought to be possible in every such case to discover sufficient as to its origin and former ownership to place its bona fides beyond doubt; if not, it is best to let the apparent bargain go.

I remember, not many years ago, waiting upon a lady in a very ordinary house in a London suburb. She had replied to an advertisement in which I had offered to purchase old glass. A glance was sufficient to show me that her collection contained nothing likely to appeal to my taste. Yet I did have a find; for she had, in addition to what I saw at first, two dishes somewhat similar in shape to a large fruit dish, but with the cipher C.R. cut upon each (Fig. 36). These were actually made and presented to Queen Charlotte on a visit which Her Majesty paid to some glass-works during a tour in Ireland. Their authenticity was guaranteed by a letter from an old tutor of the Queen relating the circumstances and handing down the pieces as a relic. The owner asked £15 for them. Needless to say, they changed{150} hands, only to do so again shortly after, and this time at the enhanced and respectable figure of fifty-five guineas. In spite of their beauty and their apparent air of genuine antiquity, I should have hesitated to purchase them but for the additional evidence afforded by the letter. One cannot be too careful.

The sweetmeat glasses (Fig. 11) are particularly fine of their kind. Each has its individuality: the one has an opal-twisted stem with a “dome” foot and a finely cut edge, whilst the other displays some exquisite cutting both on the upper part and the base. These, again, are uncommon pieces, not to be met with every day nor easily procured when met. Still, they make a more frequent appearance at sales than the larger pieces. A more ordinary variety is not so high and has flat sides and cutting. A genuine specimen, though, is not to be despised, but the type is one very freely imitated.

Some fine celery bowls of the same period are worthy of note. They are excellent specimens of the art of glass-cutting both as regards design and finish, and they are somewhat rare. As much as seven or eight guineas was recently asked in the West End of London for a

FIG. 36—SPECIMENS OF IRISH GLASS.

plain example with a slight herring-bone cutting. It was certainly genuine, but was hardly a supreme specimen of the decorative cutter’s art. The price, however, will give some idea of what would be asked for such superb specimens as those reproduced in the photograph.

The Old Irish water jugs shown in Fig. 30 are of the earliest type. That on the left is the pattern most often seen and most generally copied; in fact, during the Early Victorian era most jugs were of this design. It, however, originated in the Irish factories.

The centre piece, as well as the jug on the right, are both rare; possibly the style was not often repeated. Certainly the tremendous handle placed upon the centre one gives it a most clumsy appearance, while, in regard to the one on the right, one cannot help feeling there is something wanting at the base. They were improved upon towards the middle of the nineteenth century, when smaller handles and firmer bases were added to the design.

It is curious to note how in this kind of glass the strawberry, or flat, square style of cutting, prevails. Traces of it appear upon almost every article, so that it was evidently a favourite form{152} of decoration, and was possibly regarded as a relief from the flat, scalloped, or slip cutting then in vogue.

On the plate (Fig. 33) there are examples of sugar basins or bowls, in which the cutting is of the same kind, save that the specimen on the right is “flat” cut, with cut steps. This variety is particularly rare, and consequently highly prized among collectors. They are usually of stout, heavy glass, the cutting being very deep and the edges of the “flats” sharp. These traits will, of course, not help the collector to discriminate between the veritable antique and its modern replica. But it should be borne in mind that the modern is invariably more brilliant, has a whitish look, and is “cleaner” in every detail than the real glass of this period.

It may be mentioned that the centre bowl, although particularly attractive, is by no means so rare as other specimens figured in this chapter. Indeed, pieces of this character and design are frequently to be procured. Still, a genuine piece is well worth the collector’s attention.

The same plate (Fig. 33) illustrates some rare pickle or jam jars, displaying among them all the principal cuttings then in vogue. The end{153} one on the right is the only exception, having an engraved ornamentation. These specimens are frequently copied, but originals are still to be obtained.

The Cork houses, the product of which was finer and slighter than other Irish glass, turned out a great quantity of these. Prices run from six guineas upwards. They are copied in great number in Holland, often in small sizes and with flat cutting, so that care must be taken in choosing. Unfortunately the distinctive features—design, colour, and shape—all readily lend themselves to reproduction and, with increasing skill in imitation, make it exceedingly difficult to determine between the true and the false.