Variety of Shape.

As to variety of shape, many things that were said about lines apply equally to the spaces enclosed by them. It is impossible to write of the rhythmic possibilities that the infinite variety of shapes possessed by natural objects contain, except to point out how necessary the study of nature is for this. Variety of shape is one of the most difficult things to invent, and one of the commonest things in nature. However imaginative your conception, and no matter how far you may carry your design, working from imagination, there will come a time when studies from nature will be necessary if your work is to have the variety that will give life and interest. Try and draw from imagination a row of elm trees of about the same height and distance apart, and get the variety of nature into them; and you will see how difficult it is to invent. On examining your work you will probably discover two or three pet forms repeated, or there may be only one. Or try and draw some cumulus clouds from imagination, several groups of them 186across a sky, and you will find how often again you have repeated unconsciously the same forms. How tired one gets of the pet cloud or tree of a painter who does not often consult nature in his pictures. Nature is the great storehouse of variety; even a piece of coal will suggest more interesting rock-forms than you can invent. And it is fascinating to watch the infinite variety of graceful forms assumed by the curling smoke from a cigarette, full of suggestions for beautiful line arrangements. If this variety of form in your work is allowed to become excessive it will overpower the unity of your conception. It is in the larger unity of your composition that the imaginative faculty will be wanted, and variety in your forms should always be subordinated to this idea.

Nature does not so readily suggest a scheme of unity, for the simple reason that the first condition of your picture, the four bounding lines, does not exist in nature. You may get infinite suggestions for arrangements, and should always be on the look out for them, but your imagination will have to relate them to the rigorous conditions of your four bounding lines, and nature does not help you much here. But when variety in the forms is wanted, she is pre-eminent, and it is never advisable to waste inventive power where it is so unnecessary.

But although nature does not readily suggest a design fitting the conditions of a panel her tendency is always towards unity of arrangement. If you take a bunch of flowers or leaves and haphazard stuff them into a vase of water, you will probably get a very chaotic arrangement. But if you leave it for some time and let nature have 187a chance you will find that the leaves and flowers have arranged themselves much more harmoniously. And if you cut down one of a group of trees, what a harsh discordant gap is usually left; but in time nature will, by throwing a bough here and filling up a gap there, as far as possible rectify matters and bring all into unity again. I am prepared to be told this has nothing to do with beauty but is only the result of nature's attempts to seek for light and air. But whatever be the physical cause, the fact is the same, that nature's laws tend to pictorial unity of arrangement.

Variety of Tone Values

It will be as well to try and explain what is meant by tone values. All the masses or tones (for the terms are often used interchangeably) that go to the making of a visual impression can be considered in relation to an imagined scale from white, to represent the lightest, to black, to represent the darkest tones. This scale of values does not refer to light and shade only, but light and shade, colour, and the whole visual impression are considered as one mosaic of masses of different degrees of darkness or lightness. A dark object in strong light may be lighter than a white object in shadow, or the reverse: it will depend on the amount of reflected light. Colour only matters in so far as it affects the position of the mass in this imagined scale of black and white. The correct observation of these tone values is a most important matter, and one of no little difficulty.

The word tone is used in two senses, in the first place when referring to the individual masses as to their relations in the scale of "tone values"; and secondly when referring to the musical relationship of these values to a oneness of tone idea 188governing the whole impression. In very much the same way you might refer to a single note in music as a tone, and also to the tone of the whole orchestra. The word values always refers to the relationship of the individual masses or tones in our imagined scale from black to white. We say a picture is out of value or out of tone when some of the values are darker or lighter than our sense of harmony feels they should be, in the same way as we should say an instrument in an orchestra was out of tone or tune when it was higher or lower than our sense of harmony allowed. Tone is so intimately associated with the colour of a picture that it is a little difficult to treat of it apart, and it is often used in a sense to include colour in speaking of the general tone. We say it has a warm tone or a cold tone.

There is a particular rhythmic beauty about a well-ordered arrangement of tone values that is a very important part of pictorial design. This music of tone has been present in art in a rudimentary way since the earliest time, but has recently received a much greater amount of attention, and much new light on the subject has been given by the impressionist movement and the study of the art of China and Japan, which is nearly always very beautiful in this respect.

This quality of tone music is most dominant when the masses are large and simple, when the contemplation of them is not disturbed by much variety, and they have little variation of texture and gradation. A slight mist will often improve the tone of a landscape for this reason. It simplifies the tones, masses them together, obliterating many smaller varieties. I have even heard of the tone 189of a picture being improved by such a mist scrambled or glazed over it.

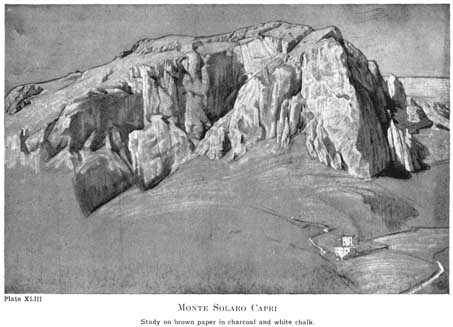

Plate XLIII.

MONTE SOLARO CAPRI

Study on brown paper in charcoal and white chalk.

The powder on a lady's face, when not over-done, is an improvement for the same reason. It simplifies the tones by destroying the distressing shining lights that were cutting up the masses; and it also destroys a large amount of half tone, broadening the lights almost up to the commencement of the shadows.

Tone relationships are most sympathetic when the middle values of your scale only are used, that is to say, when the lights are low in tone and the darks high.

They are most dramatic and intense when the contrasts are great and the jumps from dark to light sudden.

The sympathetic charm of half-light effects is due largely to the tones being of this middle range only; whereas the striking dramatic effect of a storm clearing, in which you may get a landscape brilliantly lit by the sudden appearance of the sun, seen against the dark clouds of the retreating storm, owes much of its dramatic quality to contrast. The strong contrasts of tone values coupled with the strong colour contrast between the warm sunlit land and the cold angry blue of the storm, gives such a scene much dramatic effect and power.

The subject of values will be further treated in dealing with unity of tone.

Variety in Quality and Texture

Variety in quality and nature is almost too subtle to write about with any prospect of being understood. The play of different qualities and textures in the masses that go to form a picture must be appreciated at first hand, and little can be written about it. Oil paint is capable of almost unlimited variety in this 190way. But it is better to leave the study of such qualities until you have mastered the medium in its more simple aspects.

The particular tone music of which we were speaking is not helped by any great use of this variety. A oneness of quality throughout the work is best suited to exhibit it. Masters of tone, like Whistler, preserve this oneness of quality very carefully in their work, relying chiefly on the grain of a rough canvas to give the necessary variety and prevent a deadness in the quality of the tones.

But when more force and brilliancy are wanted, some use of your paint in a crumbling, broken manner is necessary, as it catches more light, thus increasing the force of the impression. Claude Monet and his followers in their search for brilliancy used this quality throughout many of their paintings, with new and striking results. But it is at the sacrifice of many beautiful qualities of form, as this roughness of surface does not lend itself readily to any finesse of modelling. In the case of Claude Monet's work, however, this does not matter, as form with all its subtleties is not a thing he made any attempt at exploiting. Nature is sufficiently vast for beautiful work to be done in separate departments of vision, although one cannot place such work on the same plane with successful pictures of wider scope. And the particular visual beauty of sparkling light and atmosphere, of which he was one of the first to make a separate study, could hardly exist in a work that aimed also at the significance of beautiful form, the appeal of form, as was explained in an earlier chapter, not being entirely due to a visual but to a mental perception, into which the sense 191of touch enters by association. The scintillation and glitter of light destroys this touch idea, which is better preserved in quieter lightings.

There is another point in connection with the use of thick paint, that I don't think is sufficiently well known, and that is, its greater readiness to be discoloured by the oil in its composition coming to the surface. Fifteen years ago I did what it would be advisable for every student to do as soon as possible, namely, make a chart of the colours he is likely to use. Get a good white canvas, and set upon it in columns the different colours, very much as you would do on your palette, writing the names in ink beside them. Then take a palette-knife, an ivory one by preference, and drag it from the individual masses of paint so as to get a gradation of different thicknesses, from the thinnest possible layer where your knife ends to the thick mass where it was squeezed out of the tube. It is also advisable to have previously ruled some pencil lines with a hard point down the canvas in such a manner that the strips of paint will cross the lines. This chart will be of the greatest value to you in noting the effect of time on paint. To make it more complete, the colours of several makers should be put down, and at any rate the whites of several different makes should be on it. As white enters so largely into your painting it is highly necessary to use one that does not change.

The two things that I have noticed are that the thin ends of the strips of white have invariably kept whiter than the thick end, and that all the paints have become a little more transparent with time. The pencil lines here come in useful, as they can be seen through the thinner portion, and show to what 192extent this transparency has occurred. But the point I wish to emphasise is that at the thick end the larger body of oil in the paint, which always comes to the surface as it dries, has darkened and yellowed the surface greatly; while the small amount of oil at the thin end has not darkened it to any extent.

Claude Monet evidently knew this, and got over the difficulty by painting on an absorbent canvas, which sucks the surplus oil out from below and thus prevents its coming to the surface and discolouring the work in time. When this thick manner of painting is adopted, an absorbent canvas should always be used. It also has the advant............