The Caves of France, Baume, of Périgord.—Caves and Rock-shelters of Belgium, Trou de Naulette.—Caves of Switzerland.—Cave-dwellers and Pal?olithic Men of River-deposits.—Classification of Pal?olithic Caves.—Relation of Cave-dwellers to Eskimos.—Pleistocene animals living north of Alps and Pyrenees.—Relation of Cave to River-bed Fauna.—The Atlantic Coastline.—Distribution of Pal?olithic Implements.

The Caves of France.

The caves of France have been proved, by the explorations carried on during the course of the present century, to contain the same animals, introduced under the same conditions as those which we have already described. Some species, however, have been met with which have not been discovered in this country. In the cave of Lunel-viel, for example, the common striped hy?na of Africa (Hy?na striata) has been found by Marcel de Serres, to whom belongs the credit of being the first systematic explorer of caverns in France. In that of Bruniquel, the ibex, now found only in the higher mountains in Europe, the chamois and the Antelope saiga, an animal337 inhabiting the plains of the region of the Volga and of southern Siberia, have been identified by Prof. Owen; while in the collection obtained by Mr. Moggridge from the caves of Mentone, Prof. Busk has recognized the marmot. With these exceptions there is no distinction between the faunas of the bone-caves of this country and of France.219

The Cave of Baume.

The Machairodus latidens,220 or great sabre-toothed feline of Kent’s Hole, has been discovered in the cave of Baume in the Jura, according to M. Gervais,221 along with the horse, ox, wild-boar, elephant, a non-tichorhine species of rhinoceros, the spotted hy?na, and the cave-bear, or the same group of animals as that with which it is found in Kent’s Hole. The cave is considered by M. Lartet222 to be of preglacial age.

The Caves of Périgord.

The caves and rock-shelters of Périgord, explored by the late M. Lartet and our countryman, Mr. Christy,338223 1863–4, have not only afforded cumulative proof of the co-existence of man with the extinct mammalia, but have given us a clue as to the race to which he belonged. They penetrate the sides of the valleys of the Dordogne and Vezère at various levels, as may be seen in Fig. 71, and are full of the remains left behind by their ancient inhabitants, which give as vivid a picture of the human life of the period, as that revealed of Italian manners in the first century by the buried cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. The old floors of human occupation consist of broken bones of animals killed in the chase, mingled with rude implements, weapons of bone, and unpolished stone, and charcoal and burnt stones which point out the position of the hearths.

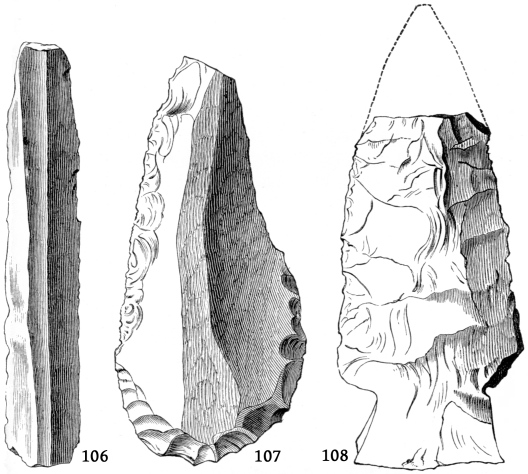

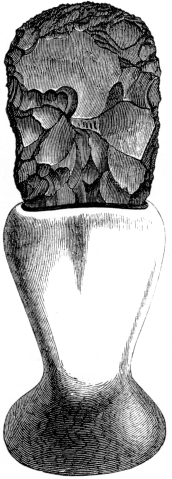

Flakes (Fig. 106) without number, rude stone-cutters, awls, lance-heads, hammers, saws made of flint or of chert, rest pêle-mêle with bone needles, sculptured reindeer antlers, engraved stones, arrow-heads, harpoons, and pointed bones, and with the broken remains of the animals which had been used as food, the reindeer, bison, horse, the ibex, the saiga antelope, and the musk sheep. In some cases the whole is compacted by a calcareous cement into a hard mass, fragments of which are to be seen in the principal museums of Europe. This strange accumulation of débris marks, beyond all doubt, the place where ancient hunters had feasted, and the broken bones and implements are merely the refuse cast aside. The reindeer formed by far the larger portion of the food, and must have lived in enormous herds at that time in the centre of France. The severity of the climate at the time may be inferred by the presence of this animal, as well as by the accumulation of bones on the spots on which man had fixed his habitation. Indeed, had not this been the339 case, the decomposition of so much animal matter would have rendered the place uninhabitable even by the lowest savage.

Fig. 106.—Flint-flake, Les Eyzies (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Fig. 107.—Flint Scraper, Les Eyzies (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Fig. 108.—Flint Javelin-head, Laugerie Haute (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Besides the animals mentioned above, the cave-bear and lion have been met with in one, and the mammoth in five localities, and their remains bear marks of cutting or scraping, which show that they fell a prey to hunters. The Irish elk, also, and the hy?na occur respectively in the cave of Laugerie Basse, and of Moustier, but the latter certainly did not gain access to the refuse-heaps, because the vertebr? are intact which it is in the habit of eating.340 For the same reason also, M. Lartet infers that the hunters were not aided in the chase by the dog. There is no evidence that they were possessed of any domestic animal. There were no spindle wheels to indicate a knowledge of spinning, nor potsherds to show an acquaintance with the potter’s art. In both these respects they resemble the Fuegians, Eskimos, and Australians, and contrast strongly with the neolithic races.

Fig. 109.—Flint Arrow-head, Laugerie Haute (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Fig. 110.—Bone needle, La Madelaine (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

The broken bones show that the reindeer furnished the more usual food, and next to that the horse, and then the bison. And from the absence of the vertebr? and pelvic bones of the two latter animals, M. Lartet concludes that they were cut up where they were killed, and the meat stripped from the backbone and the pelvis. Their food was probably cooked by boiling, the number of round stones used for heating water and bearing341 marks of fire, like the “pot boilers” of some of the American Indians, being very considerable.

Among the stone implements flint flakes were incredibly numerous, and the number of chips scattered about as well as the blocks of flint from which they had been struck, proved that they had been made on the spot; most of these flakes were notched by use (Fig. 106). Instruments with the ends carefully rounded off (Fig. 107) were also abundant, and from their analogy with similar instruments used by the Eskimos, there can be but little doubt that they were intended for the preparation of skins (compare Fig. 107 with Fig. 124). The ends of some were chipped to a point for insertion into a handle, while others rounded at both ends were probably used freely in the hand. In the cave of Moustier oval implements were met with, resembling those figured from the caverns of Kent’s Hole and Wookey (Figs. 84 and 97). The spear, javelin, and arrow-heads of flint presented two modes of attachment to the shaft, the base of some being squared off with a notch above for the ligature (as in Fig. 108), while in others (Fig. 109) it tapered off into a point intended for insertion. This latter form has been obtained also in Kent’s Hole.

The bone needles are carefully smoothed, and were pierced with a neatly-made eye (Fig. 110) by means of pointed flakes which were found along with them, and the use of which M. Lartet demonstrated by experiment. They had been sawn out of the compact metacarpals and tarsals of the reindeer224 and the horse, and subsequently rounded on fragments of sandstone, the grooves of which fitted them. In this, therefore,342 we have not merely the evidence that the hunters were in the habit of sewing, but also we have vividly brought before us the very method by which their needles were manufactured. They were probably used for sewing skins together, the tendon of a reindeer forming the thread, as among the modern Eskimos.

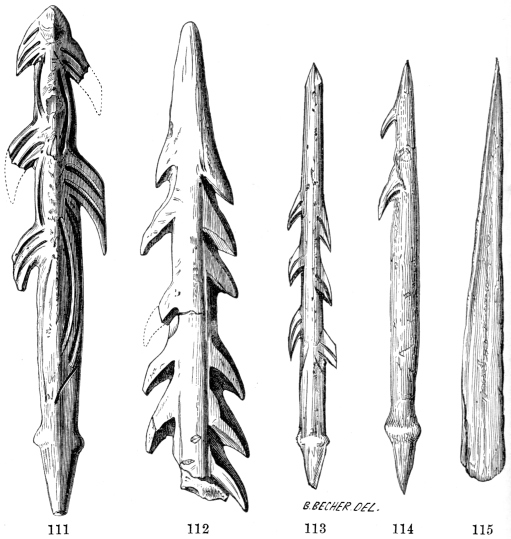

Figs. 111, 112.—Harpoons of Antler, La Madelaine. (Lartet and Christy.)

Figs. 113, 114.—Arrow-heads, Gorge d’Enfer. (Broca.)

Fig. 115.—Bone Awl, Gorge d’Enfer (1/1). (Broca.)

The heads of arrows and lances are made principally out of reindeer antler, and are barbed, the barbs generally being grooved, and carved on both sides of the axis343 (Figs. 111, 112, 113); but in some cases, as in Fig. 114, the barbs are only on one side. Many bones and antlers are variously carved into shapes for which it is impossible to assign a definite use. Fig. 115 is a bone awl.

Fig. 116.—Carved Handle of Reindeer Antler (1/2). (Lartet and Christy.)

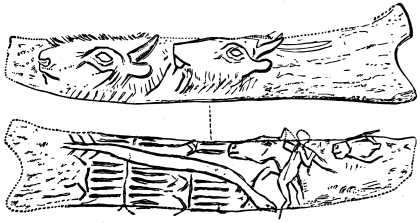

Fig. 117.—Two sides of Reindeer Antler, La Madelaine (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

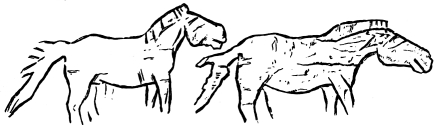

Fig. 118.—Horses engraved on Antler, La Madelaine (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

The most remarkable remains left behind by man in these refuse-heaps are the sculptured reindeer antlers, and the figures engraved on fragments of schist and on ivory. A well-defined outline of an ox stands out boldly from one piece of antler. A second presents us with a most elegant design: a reindeer is kneeling down in an easy attitude with its head thrown up in the air, so that the antlers rest on the shoulders, and the back of the animal forms an even surface for a handle, which is too small to be grasped in an ordinary European hand (Fig. 116). In a third a man stands close to a horse’s head, and hard by is a fish like an eel; and on the other side of the same cylinder are two heads of bison, drawn with sufficient clearness to ensure recognition by anyone who had ever seen that animal (Fig. 117). On a fourth the natural curvature of one of the tines has been taken advantage of by the artist to engrave the head, and the characteristic recurved horns of the ibex; and on a fifth are figures of horses (Fig. 118), in which the upright disheveled mane and shaggy ungroomed tail are represented with admirable spirit. At first sight it would344 appear that the artist had drawn the heads out of all proportion to the bodies. A horse’s skeleton, however, from the pal?olithic “station” at Solutré, lately set up in the Museum at Lyons, proves that this is not the case, since, as M. Lortet pointed out to me, it is remarkable for its massive head, and small body. In Fig. 119 a group of reindeer are seen, two on their backs, and two in the act of walking. The Irish elk, red-deer, and probably rhinoceros, are also depicted, the figures upon the hard schist being feebly and uncertainly drawn, as might be expected from the character of the tools. The most clever sculptor of modern times would, probably, not succeed very much better if his graver was a splinter of flint, and stone and bone were the materials to be engraved. One peculiarity runs through the figures of animals. With but two exceptions none345 of the feet are represented, a circumstance which is probably due, as Mr. Franks has suggested to me, to the fact that the hunters merely represented what they saw of the animal, of which the feet would be concealed by the herbage.

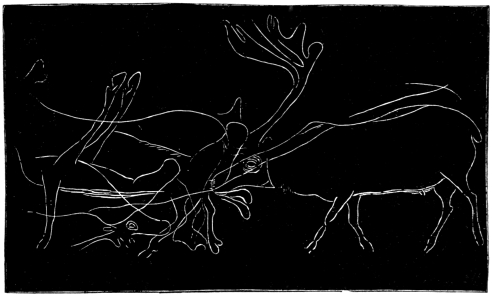

Fig. 119.—Group of Reindeer, Dordogne. (Broca.)

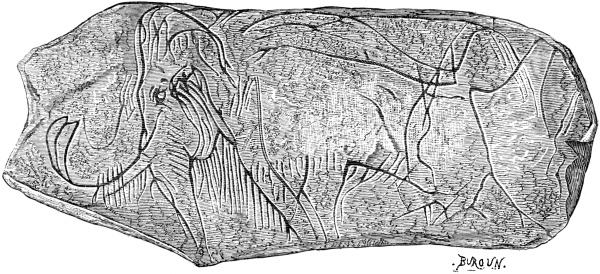

The most striking figure that has been discovered is that of the mammoth,225 Fig. 120, engraved on a fragment of its own tusk, the peculiar spiral curvature of the tusk and the long mane, which are not now to be found in any living elephant, proving that the original was familiar to the eye of the artist. The discovery of whole carcases of the animal in northern Siberia, preserved from decay in the frozen cliffs and morasses, has made us acquainted with the existence of the long hairy mane. Had not it thus been handed down to our eyes, we should probably have treated this most accurate drawing as a mere artist’s freak. Its peculiarities are so faithfully depicted that it is quite impossible346 for the animal to be confounded with either of the two living species. These drawings probably employed347 the idle hours of the hunter, and perpetuate the scenes which he witnessed in the chase. They are full of artistic feeling, and are evidently drawn from life. The mammoth is engraved on its own ivory, the reindeer generally on reindeer antler, and the stag on stag antler.

Fig. 120.—Mammoth engraved on Ivory, La Madelaine (1/2). (Lartet and Christy.)

From all these facts we must picture to our minds, that these ancient dwellers in the caves of Aquitaine lived by hunting and fishing, that they were acquainted with fire, and that they were clad with skins sewn together with sinews or strips of intestines. That they did not possess the dog is shown, not merely by the negative evidence of its not having been discovered, but also by the fact that the bones which it invariably eats, such as the vertebr?, are preserved. They did not possess any domestic animals, and there is no evidence that they were acquainted with the potter’s art. M. de Mortillet’s view, that the art of making pottery was unknown in the pal?olithic age, seems to me to be probably true, the reputed cases of the discovery of potsherds being always connected with suspicious circumstances, which render it probable that they were subsequently introduced.

Besides the remains of the animals in the refuse-heaps were fragmentary portions of human skeletons, which, however, were not scraped or broken so as to imply the practice of cannibalism.

Caves of Belgium.

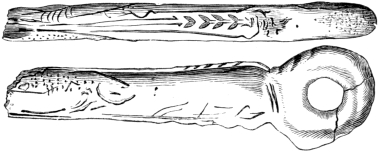

Fig. 121.—Carved Implement of Reindeer Antler, Goyet (1/2). (Dupont.)

The researches of Dr. Schmerling226 into the caves of Belgium, in 1829–30, revealed the fact that the animals348 so abundant in the caves of Germany, were equally numerous in those in the neighbourhood of Liége, and the flint flakes, and the fragments of human bones, which he found may possibly be of pal?olithic age. He also discovered the remains of the porcupine, a species no longer living north of the Alps and Pyrenees. The systematic exploration, however, of the pal?olithic caves in that district was not carried out until, in the year 1864, M. Dupont227 began the investigation of those in the neighbourhood of Dinant-sur-Meuse, on behalf of the Belgian Government. His results, based upon the examination of upwards of twenty caves and rock-shelters, are published in a series of papers read before the Royal Academy of Belgium and subsequently in a separate work. Besides the remains of the animals living in Belgium within the historic period, he met with the ibex, chamois, and marmot, which are now to be found only in the mountainous districts of Europe, the tailless hare, lemming, and arctic fox, of the northern regions, the Antelope saiga, grizzly bear, lion, hy?na, and others. Most of these species occurred in refuse accumulations, their remains being in the fragmentary condition of those of the French caves. The349 associated implements are of the same type as those of Périgord, and some of them are ornamented in the same manner as, for example, that from the cavern of Goyet, Fig. 121, termed a “baton de commandement,” but which, from its analogy with similar articles in the British Museum, is most probably an arrow-straightener. Those of flint are also of the same kind, and in several of the caves there was the same association of fragmentary human remains with the relics of the feasts as in the French refuse-heaps.

Trou de Naulette.

The human remains consisting of a lower jaw, ulna and metatarsal, discovered in the large cavern of Naulette,228 on the left bank of the Lesse, in association with the broken remains of the rhinoceros, mammoth, reindeer, chamois, and marmot, are undoubtedly of pal?olithic age, since they rested in an undisturbed stratum. M. Dupont gives the following section in descending order.

METRES.

1. Sandy grey and yellow clay 2·90

2. Yellow grey clay with stones and bones of ruminants 0·45

3. Stalagmite.

4. Tufa.

5. Three bands of clay alternating with stalagmite.

6. Sandy clay with human bones at the depth of four metres.

7. Stalagmite.

8. Cave-earth with bones gnawed by hy?nas.

The human jaw is remarkable for its prognathism, which, according to Dr. Hamy, is greater than that which350 has been observed in any living races. The cave had afforded shelter to the hy?nas before it had been used by man.

The Caves of Switzerland.

The caves of Switzerland also contain the same class of rude implements and carvings. Prof. Rupert Jones has called my attention to a recent discovery of carved reindeer antlers, and harpoon-heads, similar to those figured from the Dordogne, in a cave in the Canton of Schaaffhausen,229 along with the bones of hy?na, reindeer, and mammoth. In that of Veyrier,230 carved implements were found along with the remains of the ox, horse, chamois, and ibex, some of which, shown to me by Dr. Gosse, at the meeting of the French Association for the Advancement of Science, at Lyons in 1873, are of the same form and size as the arrow-straightener from the cave of Goyet (Fig. 121).

We may, therefore, infer that the same pal?olithic race of men once ranged over the whole region from the Pyrenees and Switzerland, as far to the north as Belgium. And since Prof. Fraas has obtained similar implements from a refuse-heap at Schussenreid in Würtemberg, they wandered as far to the east as that district, while the discoveries in Kent’s Hole and Wookey Hole prove that they extended as far to the west as Somersetshire and Devonshire.

351

Cave-dwellers and Pal?olithic Men of the River-gravels.

These pal?olithic cave-dwellers are considered by Mr. Evans231 to belong to the same race as those who have left their rude flint implements in the river-gravels in the valleys of the Thames, the Somme, the Seine, and in the eastern counties, as far to the north as Peterborough. We must, however, allow that a marked difference is to be observed between a series of flint implements found in the caves, as compared with a series found in the river-strata, although some forms are common to the two; as for instance some of those found in Brixham and Kent’s Hole. This difference can scarcely be explained on the supposition that the small things would be less likely to be preserved in the fluviatile deposits, because it leaves the rarity in the caves of the larger fluviatile forms unaccounted for. It is perhaps safer, in the present state of our knowledge, to consider the two sets to be distinct from each other. The direct superposition in Kent’s Hole of the stratum with the ordinary cave-type of implement, over that with the ordinary fluviatile type, may perhaps prove that the latter is the older.

Classification of Pal?olithic Caves.

The pal?olithic caves are divided by M. Lartet232 into four groups, according to the species of animals which they contain; into those of the age of the cave-bear, of the age of the mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, of the352 age of the reindeer, and of the age of bison. Dr. Hamy follows Sir John Lubbock,233 in considering the age of the cave-bear to be co-extensive with that of the mammoth, and in the classification of caves he adopts a series of transitions. M. Dupont divides the caves of Belgium into those belonging to the age of the mammoth, and to that of the reindeer.

It is easy to refer a given cave to the age of the reindeer or of the mammoth because it contains the remains of those animals, but the division has been rendered worthless for chronological purposes, by the fact that both these animals inhabited the region north of the Alps and Pyrenees at the same time, and are to be found together in nearly every bone-cave explored in that area. The difference between the contents of one pal?olithic cave and another, is probably largely due to the fact that man could more easily catch some animals than others, as well as to the preference for one kind of food before another. And the abundance of the reindeer, which is supposed to characterise the reindeer period, may reasonably be accounted for by the fact, that it would be more easily captured by a savage hunter, than the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, cave-bear, lion, or hy?na. The classification will apply, as I have shown in my essay on the pleistocene mammalia,234 neither to the caves of this country, of Belgium, nor of France, and my views are shared by M. de Mortillet,235 after a careful and independent examination of the whole evidence.

The division of the caves also into ages, according to353 the various types of implements found in them, proposed by M. de Mortillet, seems to be equally unsatisfactory; for there is no greater difference in the implements of any two of the pal?olithic caves, than is to be observed between those of two different tribes of Eskimos, while the general resemblance is most striking. The principle of classification by the relative rudeness, assumes that the progress of man has been gradual, and that the ruder implements are therefore the older. The difference, however, may have been due to different tribes, or families, having co-existed without intercourse with each other, as is now generally the case with savage communities; or to the supply of flint, chert, and other materials for cutting instruments, being greater in one region than in another.

Relation of Cave-dwellers to Eskimos.

Fig. 122.—Eskimos Spear-head, bone (1/2).

Fig. 123.—Eskimos Arrow-straightener of Walrus Tooth (1/1). (Brit. Mus.)

Can these cave-dwellers be identified with any people now living on the face of the earth? or are they as completely without representatives as their extinct contemporaries, the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros? Absolute certainty we cannot hope to obtain on the point, but the cumulative evidence enables an answer to be given which is probably true. Along the American shore of the great Arctic Ocean, in the region of everlasting snow, dwell the Eskimos, living by hunting and354 fishing, speaking the same language, and using the same implements from the Straits of Behring on the west, to Greenland on the east. Their implements and weapons, brought home by the arctic explorers, enable us to institute a comparison with those found in the pal?olithic caves. The harpoons in the Ashmolean collection at Oxford, brought over by Captain Beechey and Lieut. Harding from West Georgia, as well as those in the British Museum, are almost identical in shape and design with those from the caves of Aquitaine and Kent’s Hole; the only difference being that some of the latter have grooved barbs. The heads of the fowling and fishing spears, darts, and arrows, as well as the form of their bases for insertion into the shafts, are also identical (Fig. 122), as may be seen from a comparison of Fig. 122 with Figs. 99 and 114. The355 curiously carved instrument, Fig. 123, which the Eskimos use for straightening their arrows is variously ornamented with designs of animals, analogous to those cut on the reindeer antlers in Aquitaine; and if it be compared with the so-called “baton de commandement,” Fig. 121, it will be seen, that the latter also was probably intended for the same purpose; the difference in the shape of the hole in the two figured specimens being also observable in the series of Eskimos arrow-straighteners in the British Museum, and being largely due to friction by use. Many of the implements are the same in form. An Eskimos stone scraper for preparing skins, or plane for smoothing wood, is represented in Fig. 124, which is inserted in a handle of fossil mammoth ivory, obtained from the frozen ice-cliffs on the shores of the Arctic sea. If it be compared with Fig. 107 from the caves, it will be seen to be of the same pattern. It is indeed not a little singular, that the handle in which it is imbedded should have been formed out of the tusks of the same species of elephant as that which was depicted by the pal?olithic hunter (see Fig. 120), in the south of France.

Fig. 124.—Eskimos Plane or Scraper (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Some of the Eskimos lance-heads of stone in the British Museum are of the same type as that figured from the caves of the Dordogne (Fig. 108).

356 The most remarkable objects brought home from the northern regions are the implements of bone and antler which are ornamented with the figures of animals hunted by the Eskimos on sea or land. On the side of one bow in the Ashmolean Museum, used for drilling holes, you see them harpooning the whale from their skin boats, and catching birds. On a second they are harpooning walrus and catching seals; on a third the seals are being dragged home. The huts in which they live, the tethered dogs, the boat supported on its platform, and their daily occupations are faithfully represented. One bow is ornamented with a large number of porpoises, while on another is a reindeer hunt in which the animals are being attacked while they are crossing a ford. On a bone implement in the British Museum from Fort Clarence, the reindeer are being shot down by archers (Fig. 125). The arrow straightener, Fig. 123, is adorned with a reindeer hunting scene, in which the animals are seen browsing and unsuspicious of the approach of the hunters, who are advancing, clad in reindeer skins and wearing antlers on their heads.

A comparison of these various designs with those from the caves of France and Belgium shows an identity of plan and workmanship, with this difference only, that the hunting scenes familiar to the pal?olithic cave-dweller were not the same as those familiar to the Eskimos on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Each sculptured the animals he knew, and the whale, walrus, and seal were unknown to the inland dwellers in Aquitaine, just as the mammoth, bison, and wild horse are unknown to the Eskimos. The reindeer, which they both knew, is represented in the same way by both. The West Georgians made their dirks of walrus tooth, and ornamented357 them with carvings of the backbones of fishes; the people of Aquitaine used for the same purpose reindeer antlers, and ornamented them with figures of that animal (see Fig. 116). And it is worthy of remark that the latter had sufficient artistic feeling to depict the mammoth on mammoth ivory, the reindeer generally on reindeer antler, and the stag on its own antler.

Fig. 125.—Eskimos Hunting-scene (1/1). (Fort Clarence.)

An appeal to the habits of these two peoples, now separated by so wide an interval of space and time, tends also to show that they are descended from the same stock. The method of accumulating large quantities of the bones of animals around their dwelling-places, and the habit of splitting the bones for the sake of the marrow, is the same in both. Their hides were prepared by the same sort of instruments and in the same manner, and the needles with which they were sewn together are of the same pattern. The few remains of man among the relics of feasts in the caves of Belgium and France, show the same disregard of sepulture as that implied by the human skulls lying about along with numerous bones of walrus, seal, dog, bear, and fox, in an Eskimos camp in Igloolik, which were carried away by Captain Lyon, without the slightest objection on the part of the relatives of the dead.

All these facts can hardly be mere coincidences, caused by both peoples leading a savage life under similar circumstances: they afford reasons for the belief that358 the Eskimos of North America are connected by blood with the pal?olithic cave-dwellers of Europe. To the objection that savage tribes living under similar conditions use similar instruments, and that, therefore, the correspondence of those of the Eskimos with those of the reindeer folk does not prove that they belong to the same race, the answer may be made, that there are no two savage tribes now living which use the same set of implements, without being connected by blood. The agreement of one or two of the more common and ruder instruments may be perhaps of no value in classification, but if a whole set agree, fitted for various uses, and some of them rising above the most common wants of savage life, we must admit that the argument as to race is of very great value. The implements found in Belgium, France, or Britain differ scarcely more from those now used in West Georgia, than the latter do from those now in use in Greenland or Melville Peninsula. The conclusion, therefore, seems inevitable, that so far as we have any evidence of the race to which the dwellers in the Dordogne belong, that evidence points only in the direction of the Eskimos.

This conclusion is to a great extent confirmed by a consideration of the animals found in the caves. The reindeer and the musk sheep afford food to the Eskimos now, just as they afforded it to the pal?olithic hunters in Europe. No naturalist would deny that the pleistocene musk sheep is of the same species as that of North America, and although the animal is extinct in Europe and Asia, its remains, scattered through Germany, Russia in Europe, and Siberia, show that it formerly ranged in the whole of that area. The enormous distance, therefore, of southern France from the northern shores of America,359 cannot be considered as an obstacle to this view, for, to say the least, pal?olithic man would have had the same chance of retreating to the north-east as the musk sheep. The mammoth and bison have also been tracked by their remains in the frozen river gravels and morasses through Siberia, as far to the north-east as the American side of the Straits of Behring. Pal?olithic man appeared in Europe with the arctic mammalia, lived in Europe along with them, and disappeared with them. And since his implements are of the same kind as those of the Eskimos, it may reasonably be concluded that he is represented at the present time by the Eskimos, for it is most improbable that the convergence of the ethnological, and zoological evidence should be an accident. These views,236 which I advanced in 1866, have been to a great extent accepted by Sir John Lubbock in his last edition of Prehistoric Man.

Pleistocene Animals living to the North of the Alps and Pyrenees.

The principal mammalia inhabiting Britain, France, and Germany during the pleistocene age, and contemporary with man in Europe, are given in the following table, which shows that the fauna of the region to the north of the Alps and Pyrenees was remarkably uniform. The cave-fauna of Provence, Italy, and Spain, will be treated of in the next chapter.

360

(Image of Table)

Species. Gailenreuth Cave Kirkdale Victoria Cefn Plas-

newydd Plas Heaton Gallfaenan Paviland Bacon’s Hole Minchin Hole Bosco’s Den Crow Hole Ravenscliff Spritsail Tor Long Hole Blackrock Fissure Caldy Fissure Coygan Cave Hoyle Cave King Arthur’s Cave

Homo pal?olithicus—Pal?olithic Man x x x x x x

Spermophilus citillus—Pouched Marmot

Arctomys marmotta—Common Marmot

Castor fiber—Beaver

Lepus timidus—Hare x x x

Lepus variabilis—Alpine Hare

Lepus cuniculus—Rabbit x x x

Lepus diluvianus—Extinct Hare

Lagomys pusillus—Tailless Hare

Mus lemmus—Lemming

Hystrix dorsata—Porcupine x

Felis leo (var. spel?a)—Lion x x x x x x

Felis pardus—Leopard

Felis Lynx—Lynx

Felis caffer—Caffir Cat

Felis catus—Wild Cat x x x

Machairodus latidens

Gulo borealis—Glutton x x

Hy?na crocuta (var. spel?a)—Spotted Hy?na x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Hy?na striata—Striped Hy?na

Mustela martes—Marten x x x

Mustela putorius—Polecat x x x

Mustela erminea—Weasel x x

Lutra vulgaris—Otter x

Ursus arctos—Brown Bear x x x ............