The Caves of Paviland.—Engis.—Trou du Frontal.—Gendron.—Neanderthal.—Gailenreuth.—Aurignac.—Bruniquel.—Cro-Magnon.— Lombrive.—Cavillon, near Mentone.—Grotta dei Colombi in Island of Palmaria, inhabited by Cannibals.—General Conclusions.

There are many prehistoric caves in Britain and on the Continent which do not contain remains sufficiently characteristic to fix the date of their use, either for occupation or burial, unless the term neolithic be understood to cover the wide interval between the pal?olithic stage of the pleistocene on the one hand, and the bronze age on the other.

The Paviland Cave.

The Cave of Goat’s Hole155 at Paviland, in Glamorganshire, explored by Dr. Buckland in 1823, offers an instance of an interment having been made in a pre-existent deposit of the pleistocene age. It consists of a chamber facing to the sea, in a cliff of limestone 100 feet high, at a level of from 30 to 40 feet above the high-water mark. Its floor was composed of red loam, containing the remains of the woolly-rhinoceros, hy?na, cave-bear,233 and mammoth. Close to a skull with tusks of the last animal a human skeleton (equalling in size the largest male skeleton in the Oxford Museum) was discovered; and in the soil, “which had apparently been disturbed by ancient diggings,” were fragments of charcoal, a small chipped flint, and the sea-shells of the neighbouring shore. Certain small ivory ornaments, found close to the skeleton, are considered by Dr. Buckland to have been carved out of the tusks of the mammoth near which they rested; and he justly remarks that, “as they must have been cut to their present shape at a time when the ivory was hard, and not crumbling to pieces, as it is at present at the slightest touch, we may from this circumstance assume for them a high antiquity.”

May we not also infer, from the fact of the manufactured ivory and the tusks from which it was cut being in precisely the same state of decomposition, that the tusks were preserved from decay, during the pleistocene times, by precisely the same agency as those now found perfect in the polar regions—namely, the intense cold; that after the skull of the mammoth had been buried in the cave, the tusks, thus preserved, were used for the manufacture of ornaments; and that, at some time subsequent to the interment of the ornaments with the corpse, a climatal change has taken place, by which the temperature in England, France, and Germany has been raised, and the ivory became decomposed that up to that time had preserved its gelatine? On this point it is worthy of remark that fossil tusks have been discovered in Scotland sufficiently perfect to be used as ivory. The ornaments may, however, not have been made from the fossil tusks.

234 The presence of the bones of sheep underneath the remains of mammoth, bear, and other animals, coupled with the state of the cave earth, which had been disturbed before Dr. Buckland’s examination of the cave, would prove that the interment is not of pleistocene date. No traces of sheep or goat have as yet been afforded by any pleistocene deposit in Britain, France, or Germany.

Dr. Buckland’s conclusion, that the interment is relatively more modern than the accumulation with remains of the extinct mammalia, must be accepted as the true interpretation of the facts. The intimate association of the two sets of remains, of widely diverse ages, in this cave show that extreme care is necessary in cave exploration.

The Cave of Engis.

Human remains have been obtained from some of the caves of Belgium under circumstances which are generally considered to indicate that they are of the same antiquity as the skeletons of the animals with which they are associated. The possibility, however, of the contents of caves of different ages being mixed by the action of water, or by the burrowing of animals, or by subsequent interments, renders such an association of little value, unless the evidence be very decided. The famous human skull discovered by Dr. Schmerling156 in the cave of Engis, near Liége, in 1833, is a case in point. It was obtained from a mass of breccia, along with bones and teeth of mammoth, rhinoceros, horse, hy?na, and bear; and subsequently235 M. Dupont157 found in the same spot a human ulna, other human bones, worked flints, and a small fragment of coarse earthenware. The discovery of this last is an argument in favour of the human remains being of a later date than the extinct mammalia, since pottery has not yet been proved to have been known to the pal?olithic races who co-existed with them, while it is very abundant in neolithic burial-places and tombs. The fact of all the objects being cemented together by calcareous infiltration is no test of relative age, which cannot be ascertained without distinct stratification, such as that in the caves of Wookey and Kent’s Hole.

It seems therefore to me, that the conditions of the discovery are too doubtful to admit of the conclusion of Sir Charles Lyell and other eminent writers, that the human remains are of pal?olithic age.

The skull is described by Professor Huxley158 as being of average size, its contour agreeing equally well with some Australian and European skulls; it presents no marks of degradation, “and is in fact a fair average human skull, which might have belonged to a philosopher, or might have contained the thoughtless brains of a savage.” Its measurements fall within the limits of the long-skulls described in the preceding chapter, and it certainly belongs to the same class.

236 The following Table will show the variation in size and form of the skulls mentioned in this chapter:

Measurements of Skulls of doubtful antiquity.

Length. Breadth. Height. Circum-

ference. Cephalic

index. Altitudinal

index.

Engis (Huxley) ?7·7? 5·4? — 20·5? ·700 —

Trou du Fronta (Pruner-Bey) ?6·9? 5·6? — 21·55 ·811 ·704

Gailenreuth (Dawkins) ?6·82 5·5? — 21·55 ·813 ·813

Neanderthal (Schaaffhausen) 12·0 5·75 — 23·?? ·720 —

Cro-Magnon, No. 1 (Broca) 7·95 5·86 — 22·36 ·730 —

” ” 2 ” 7·52 5·39 — 21·26 ·71? —

” ” 3 ” 7·94 5·94 — 22·24 ·74? —

Trou du Frontal.

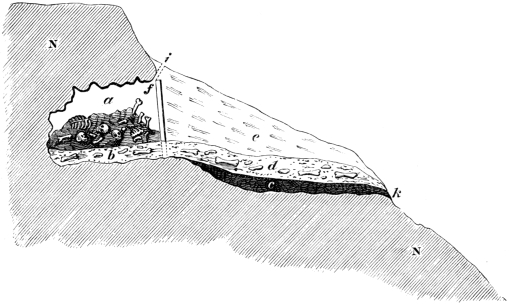

The human skeletons in the Trou du Frontal, situated in a picturesque limestone cliff on the banks of the Lesse, near Furfooz, are considered by M. Dupont to be of the same age as the contents of the caves close by the Trou des Nutons and Trou Rosette, which have been inhabited by pal?olithic savages. The following is the section (Fig. 69) which he gives of the deposits. Close to the river Lesse is the alluvium (No. 1), below which is a clay (No. 2), with angular blocks passing upwards under the rock shelter, and filling the cave. Under this is a stratum of loam (No. 3), resting on gravel (No. 4). Sixteen human skeletons were discovered in the sepulchral cavity (S), at the mouth of which was a large slab of rock (D), by which it was originally blocked up. A singular urn, with a round bottom and with the handles perforated for suspension, was found at the entrance, together with flint flakes, ornaments in fluorine, and eocene shells perforated for237 suspension. Outside, at the points H H, was an accumulation of broken bones, belonging to the lemming, tailless hare (Lagomys), beaver, wild cat, boar, horse, stag, urus, chamois, goat, and other animals, birds and fishes. From the occurrence of fragments belonging to two reindeer, it is considered by M. Dupont to belong to the reindeer age. The old hearth was close by, at F (Fig. 69).

Fig. 69.—Section of the Trou du Frontal. (Dupont.)

From this section we may infer, that the rock-shelter was used by man at the points H H and F before the formation of the stratum No. 2, which is probably merely subaerial rain-wash, due to the disintegration of the adjacent rocks, and that the sepulchral cavity was a place of burial either before, or while No. 2 was accumulated. Can we further conclude that there is any necessary connection between the refuse-heap and the sepulchre in point of time? M. Dupont holds that the contents of all the caves in the cliff are pal?olithic, and238 that the sepulchral cavity is therefore of that age.159 It seems to me, however, that the evidence in favour of this view is not conclusive. The burial place may have belonged to one people, and the refuse-heaps in the neighbouring caves and outside the slab in the rock-shelter of the Trou du Frontal to another. The form of the urn is remarkably like some of those which have been obtained from the neolithic pile-dwellings of Switzerland, and therefore may possibly imply that the interment is of that age.

The human remains were mixed pêle mêle with stones and yellow clay within the chamber. Two skulls, sufficiently perfect to allow of measurement, show that their possessors were broad-headed (brachy-cephalic), and of the same type as those of Sclaigneaux. They are considered by the late Dr. Pruner-Bey to belong to the “type Mongoloide,” and are believed by M. Dupont to prove that the pal?olithic inhabitants of Belgium were a Mongoloid race. They seem, however, to be of the same general order as the broad-skulls from the neolithic caves and tombs of France, and from the round barrows of Great Britain, as well as those from the neolithic tombs of Borreby and Mo?n in Scandinavia. And they are looked upon by MM. de Quatrefages, Virchow, and Lagneaux,160 as presenting the same type as that which is to be recognized in the present population of Belgium, in the neighbourhood, for example, of Antwerp.

These affinities may be explained by the view advanced by Dr. Thurnam, that the broad-heads of the British, French, and Scandinavian tombs are cognate239 with the modern Fin; or by the higher generalisation of Prof. Huxley, that the Swiss “Dissentis” skull, the South German, the Sclavonian, and the Finnish, belong to one great race of fair-haired, broad-headed, Xanthochroi “who have extended across Europe from Britain to Sarmatia, and we know not how much further to the east and south.”161

Besides these broad crania, M. Lagneaux162 calls attention to a fragment, sufficiently perfect to indicate a skull of the long type (très dolicho-céphale), and that differed from them in many other particulars. In the Trou du Frontal, therefore, there is proof that a long and a short-headed race lived in Belgium side by side, just as a similar association in the cave of Orrouy establishes the same conclusion as to the neolithic dwellers in France. And since skulls of both these types have been discovered in the neolithic caves of Sclaigneaux and Chauvaux, the interment in the Trou du Frontal may probably be referred to that date.

The Cave of Gendron.

The sepulchral cave of Gendron163 on the Lesse, in which fourteen skeletons were discovered lying at full length, and in regular order, along with one flake and some fragments of pottery, is of uncertain age, since those articles were found at the entrance, and have no necessary connection with the interments. And if they were deposited at the same time, M. Dupont’s view that they stamp the neolithic age is rendered untenable by240 the fact that flakes and rude pottery were in use as late as the date of the Roman conquest of Britain, and are frequently met with in association with articles of bronze and of iron. And for the same reasons the neolithic age of the human bones in the Trou de Sureau and of the Trou de Pont-à-Lesse is open to considerable doubt. The contents, however, prove these caves to be post-pleistocene.

Cave of Gailenreuth.

The same uncertainty overhangs the age of the interments in the cave of Gailenreuth, in Franconia, from which Dr. Buckland164 obtained a human skull of the same broad type as that from Sclaigneaux, along with fragments of black coarse pottery, one of which is ornamented with a line of finger-impressions. The skull is remarkable for the great width of the parietal protuberances, and the flattening of the upper and posterior region of the parietal bone. Its measurements are given in the Table, p. 236, from which it will be seen that it belongs to the same class of skulls as those from the neolithic caves and tumuli of France.

Cave of Neanderthal.

The extraordinary skull found in 1857 in the cave of Neanderthal,165 by Dr. Fuhlrott, with some of the other bones of the skeleton, was not associated with any other241 animals from which its age could be inferred. “Under whatever aspect,” writes Professor Huxley, “we view this cranium, whether we regard its vertical depression, the enormous thickness of its supraciliary ridges, its sloping occiput, or its long and straight squamosal suture, we meet with ape-like characters, stamping it as the most pithecoid of human crania yet discovered. But Prof. Schaaffhausen states that the cranium, in its present condition, holds 1033·24 cubic centimetres of water, or about 63 cubic inches, and as the entire skull could hardly have held less than an additional 12 cubic inches, its capacity may be estimated at about 75 cubic inches, which is the average capacity given by Morton for Polynesian and Hottentot skulls.

So large a mass of brain as this would alone suggest that the pithecoid tendencies, indicated by this skull, did not extend deep into the organization, and this conclusion is borne out by the dimensions of the other bones of the skeleton, given by Prof. Schaaffhausen, which show that the absolute height and relative proportions of the limbs were quite those of a European of middle stature. The bones are indeed stouter, but this, and the great development of the muscular ridges noted by Dr. Schaaffhausen, are characters to be expected in savages. The Patagonians, exposed without shelter or protection to a climate possibly not very dissimilar from that of Europe at the time during which the Neanderthal man lived, are remarkable for the stoutness of their limb-bones.

In no sense, then, can the Neanderthal bones be regarded as the remains of a human being intermediate between men and apes; at most they demonstrate the existence of a man whose skull may be said to revert242 somewhat towards the pithecoid type—just as a carrier, or a poulter, or a tumbler may sometimes put on the plumage of its primitive stock, the Columba livia.”

This skull, like the preceding, belongs to the dolicho-cephalic division, reaching the enormous length of twelve inches, with a parietal breadth of 5·75.

A long-skull found near Ledbury Hill in Derbyshire, and belonging to the river-bed type of Prof. Huxley, comes so close to this one of Neanderthal, that were it flattened a little and elongated, and possessed of larger supraciliary ridges, it would be converted into the nearest likeness which has yet been discovered.166

The Caves of France.—Aurignac.

In the cave of Neanderthal, the question of the antiquity of the human remains is not complicated by the juxtaposition of extinct pleistocene animals or of pal?olithic implements. Those caves, however, in France which claim especial attention, Aurignac, Bruniquel, and Cro-Magnon, are equally famous for their interments, and the pal?olithic implements which they have furnished, along with the remains of the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and other extinct animals.

They have both been inhabited by pal?olithic man, and been used some time for burial. Does the period of habitation coincide with that of the burial? This important question has been answered almost universally in the affirmative, and the interments are viewed as evidence of a belief in the supra-natural among the most ancient inhabitants of Europe, as well as offering examples of their physique.

243 The famous cave of Aurignac, near the town of that name, in the department of the Haute Garonne, was explored and described by the late M. Ed. Lartet, and his conclusions were adopted by Sir Charles Lyell in the first three editions of the “Antiquity of Man.” In the fourth edition,167 however, the latter author, after a reconsideration of all the circumstances, qualifies his acceptance of the pal?olithic age of the interments, and shares the doubts which have been expressed by Sir John Lubbock and Mr. John Evans. The evidence is as follows:—

M. Lartet’s account falls naturally into two parts: first, the story which he was told by the original discoverer of the cave; and, secondly, that in which the results of his own discoveries are described. We will begin with the first. In the year 1852, a labourer, named Bonnemaison, employed in mending the roads, put his hand into a rabbit-hole (Fig. 70, f), and drew out a human bone, and having his curiosity excited, he dug down until, as his story goes, he came to a great slab of rock. Having removed this, he discovered on the other side a cavity seven or eight feet in height, ten in width, and seven in depth, almost full of human bones, which Dr. Amiel, the Mayor of Aurignac, who was a surgeon, believed to represent at least seventeen individuals. All these human remains were collected, and finally committed to the parish cemetery, where they rest to the present day, undisturbed by sacrilegious hands. Fortunately, however, Bonnemaison in digging his way into the grotto, had met with the remains of extinct animals, and works of art; and these were244 preserved until, in 1860, M. Lartet accidentally heard of the discovery, and investigated the circumstances on the spot. He found that Bonnemaison, and the sexton who had buried the human remains, had taken so little note of the place where they were interred, that it could not be identified, and on examining the cave he found that the interior had been ransacked, and the original stratification to a great extent disturbed. M. Lartet’s exploration showed that a stratum containing the remains of the cave-bear, lion, rhinoceros, hy?na, mammoth, bison, horse, and other animals, and pal?olithic implements, like those of Périgord, extended from the plateau (d) outside into (b) the cave. On the outside he met with ashes, and burnt and split bones, which proved that it had been used as a feasting-place by the pal?olithic hunters; within he detected no traces of charcoal, and no traces of the hy?nas, which were abundant outside. Inside he met with a few human bones in the earth which Bonnemaison had disturbed, which were in the same mineral condition as those of the extinct animals, and he, therefore, inferred that they were of the same age. Such is the summary of the facts which M. Lartet discovered. He has, of his own personal knowledge, only proved that Aurignac was occupied by a tribe of hunters during the pal?olithic age, and that it had been used as a burial-place.

Fig. 70.—Diagram of the Cave of Aurignac.

Is he further justified in concluding that the period of pal?olithic occupation coincides with that in which the burial took place? Bonnemaison’s recollections may be estimated at their proper value by the significant fact, that, in the short space of eight years intervening between the discovery and the exploration, he had forgotten where the skeletons had been buried. And245 even if his account be true in the minutest detail, it does not afford a shadow of evidence in favour of the cave having been a place of sepulchre in pal?olithic times, but merely that it had been so used at some time or another. If we turn to the diagram constructed by M. Lartet to illustrate his views (“Ann. des Sc. Nat. Zool.,” 4e sér., t. xv., pl. 10), and made for the most part from Bonnemaison’s recollections; or to the amended diagram (Fig. 70) given by Sir Charles Lyell (“Antiquity of Man,” 1st ed., Fig. 25), we shall see that the skeletons are depicted above the stratum (b) containing the pal?olithic implements and pleistocene mammalia; and therefore, according to the laws of geological evidence, they must have been buried after the subjacent deposit was accumulated. The previous disturbance of the cave-earth does away with the conclusion, that the few human bones found by M. Lartet are of the same age as the extinct mammalia in the deposit. The absence of charcoal inside was quite as likely to be246 due to the fact that a fire kindled inside would fill the grotto with smoke, while outside the pal?olithic savage could feast in comfort, as to the view that the ashes are those of funereal feasts in honour of the dead within, held after the slab had been placed at the entrance. The absence of the remains of hy?nas from the interior is also negative evidence, disproved by subsequent examination.

The researches of the Rev. S. W. King, in 1865, complete the case against the current view of the pal?olithic character of the interments, since they show that M. Lartet did not fully explore the cave, and that he consequently wrote without being in possession of all the facts. The entrance was blocked up, according to Bonnemaison, by a slab of stone, which, if the measurements of the entrance be correct, must have been at least nine feet long and seven feet high, placed, according to M. Lartet, to keep the hy?nas from the corpses of the dead. It need hardly be remarked, that the access of these bone-eating animals to the cave would be altogether incompatible with the preservation of the human skeletons, had they been buried at the same time. The enormous slab was never seen by M. Lartet, and it did not keep out the hy?nas. In the collection made by the Rev. S. W. King from the interior there are two hy?nas’ teeth, and nearly all the antlers and bones bear the traces of the gnawing of these animals. The cave, moreover, has two entrances instead of one, as M. Lartet supposed when his paper in the “Annales” was published. The bones of the sheep, or goat, also obtained from the inside, and preserved in the Christy Museum, afford strong evidence that the interment is not pal?olithic; and a fragment of pottery, agreeing exactly with that247 used in the neolithic age, probably indicates its relative antiquity. This conclusion has also been arrived at by the two most recent explorers, MM. Cartaillac and Gautier.

The skeletons, therefore, in the Aurignac cave cannot be taken to be of the same age as the stratum on which they rested; but, so far as there is any evidence, may probably be referred to the neolithic age, in which the custom of burial in caves prevailed throughout Europe.

Cavern of Bruniquel.

The famous cavern of Bruniquel, explored by the Vicomte de Lastic in 1863–4,168 and described by Professor Owen, is also one of the class which has furnished human bones, along with the remains of the extinct mammalia. It penetrates a cliff in the Jurassic limestone, opposite the little village of Bruniquel (Tarn and Garonne), about forty feet above the level of the river Aveyron. The bottom was covered with a sheet of stalagmite, resting on earth and blocks of stone, for the most part finely cemented into a breccia, that is black with the particles of carbon constituting the “limon noir” of the workmen, four or five feet thick, beneath which is the “limon rouge,” or red earth without charcoal, from three to four feet thick. Every part of the breccia is charged with the broken remains of the wolf, rhinoceros, horse, reindeer, stag, Irish elk and bison, and pal?olithic implements of flint and bone; some of the latter having well-executed designs of the heads of horses and reindeer, which prove that the cave had been used as a place of habitation by the hunters of those animals. Imbedded in the breccia at a depth of from three to five feet human bones were met248 with, and in two recesses several individuals, including a child, were found, one of which Professor Owen and the Vicomte de Lastic disinterred with sufficient care to prove that the body had been buried in the crouching posture. The only calvarium sufficiently perfect to allow of a comparison belonged to the dolicho-cephalic type, and was very fairly developed.

Join or Log In!

You need to log in to continue reading