Chap. ii.

On the Magnetick Coition, and first on the Attraction of Amber, or more truly, on the Attaching of Bodies to Amber.

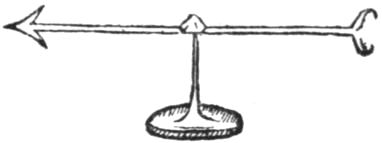

C elebrated has the fame of the loadstone and of amber ever been in the memoirs of the learned. Loadstone and also amber do some philosophers invoke when in explaining many secrets their senses become dim and reasoning cannot go further. Inquisitive theologians also would throw light on the divine mysteries set beyond the range of human sense, by means of loadstone and amber; just as idle Metaphysicians, when they are setting up and teaching useless phantasms, have recourse to the loadstone as if it were a Delphick sword, an illustration always applicable to everything. But physicians even (with the authority of Galen), desiring to confirm the belief in the attraction of purgative medicines by means of the likeness of substance and the familiarities of the juices — truly a vain and useless error — bring in the loadstone as witness as being a nature of great authority and of conspicuous efficacy and a remarkable body. So in very many cases there are some who, when they are pleading a cause and cannot give a reason for it, bring in loadstone and amber as though they were personified witnesses. But these men (apart from that common error) being ignorant that the causes of magnetical motions are widely different from the forces of amber, easily fall into error, and are themselves the more deceived by their own cogitations. For in other bodies a conspicuous force of attraction manifests itself otherwise than in loadstone; like as in amber, concerning which some things must first be said, that it may appear what is that attaching of bodies, and how it is different from and foreign to the magnetical actions; those mortals being still ignorant, who think that inclination to be an attraction, and compare it with the magnetick coitions. The Greeks call it ἤλεκτρον108 because it attracts straws to itself, when it is warmed by rubbing; then it is called ἅρπαξ109; and χρυσοφόρον from its golden colour. But the Moors call it Carabe110, because they are accustomed to offer the same in sacrifices and in the worship of the Gods. For Carab signifies to offer in Arabic; so Carabe, an offering: or seizing chaff, as Scaliger quotes from Abohalis, out of the Arabic or Persian language. Some also call it Amber, especially the Indian and Ethiopian amber, called in Latin Succinum, as if it were a juice111. The Sudavienses or Sudini112 call it geniter, as though it were generated terrestrially. The errors of the ancients concerning its nature and origin having been exploded, it is certain that amber comes for the most part from the sea, and the rustics collect it on the coast after the more violent storms, with nets and other tackle; as among the Sudini of Prussia; and it is also found sometimes on the coast of our own Britain. It seems, however, to be produced also in the soil and at spots of some depth, like other bitumens; to be washed out by the waves of the sea; and to become concreted more firmly from the nature and saltness of the sea-water. For it was at first a soft and viscous material; wherefore also it contains enclosed and entombed in pieces of it, shining in eternal sepulchres, flies, grubs, gnats, ants; which have all flown or crept or fallen into it when it first flowed forth in a liquid state113. The ancients and also more recent writers recall (experience proving the same thing), that amber attracts straws and chaff114. The same is also done by jet115, which is dug out of the earth in Britain, in Germany, and in very many lands, and is a rather hard concretion from black bitumen, and as it were a transformation into stone. There are many modern authors116 who have written and copied from others about amber and jet117 attracting chaff, and about other substances generally unknown; with whose labours the shops of booksellers are crammed. Our own age has produced many books about hidden, abstruse, and occult causes and wonders, in all of which amber and jet are set forth as enticing chaff; but they treat the subject in words alone, without finding any reasons or proofs from experiments, their very statements obscuring the thing in a greater fog, forsooth in a cryptic, marvellous, abstruse, secret, occult, way. Wherefore also such philosophy produces no fruit, because very many philosophers, making no investigation themselves, unsupported by any practical experience, idle and inert, make no progress by their records, and do not see what light they can bring to their theories; but their philosophy rests simply on the use of certain Greek words, or uncommon ones; after the manner of our gossips and barbers nowadays, who make show of certain Latin words to an ignorant populace as the insignia of their craft, and snatch at the popular favour. For it is not only amber and jet (as they suppose) which entice small bodies118; but Diamond, Sapphire, Carbuncle, Iris gem119, Opal, Amethyst, Vincentina, and Bristolla (an English gem or spar)120, Beryl, and Crystal121 do the same. Similar powers of attraction are seen also to be possessed by glass (especially when clear and lucid), as also by false gems made of glass or Crystal, by glass of antimony, and by many kinds of spars from the mines, and by Belemnites. Sulphur also attracts, and mastick, and hard sealing-wax122 compounded of lac tinctured of various colours. Rather hard resin entices, as does orpiment123, but less strongly; with difficulty also and indistinctly under a suitable dry sky124, Rock salt, muscovy stone, and rock alum. This one may see when the air is sharp and clear and rare in mid-winter, when the emanations from the earth hinder electricks less, and the electrick bodies become more firmly indurated; about which hereafter. These substances draw everything, not straws and chaff only125, but all metals, woods, leaves, stones, earths, even water and oil, and everything which is subject to our senses, or is solid; although some write that amber does not attract anything but chaff and certain twigs; (wherefore Alexander Aphrodiseus falsely declares the question of amber to be inexplicable, because it attracts dry chaff only, and not basil leaves126), but these are the utterly false and disgraceful tales of the writers. But in order that you may be able clearly to test how such attraction occurs127, and what those materials128 are which thus entice other bodies (for even if bodies incline towards some of these, yet on account of weakness they seem not to be raised by them, but are more easily turned), make yourself a versorium of any metal you like, three or four digits in length, resting rather lightly on its point of support after the manner of a magnetick needle, to one end of which bring up a piece of

amber or a smooth . and polished gem which has been gently rubbed; for the versorium turns forthwith. Many things are thereby seen to attract, both those which are formed by nature alone, and those which are by art prepared, fused, and mixed; nor is this so much a singular property of one or two things (as is commonly supposed), but the manifest nature of very many, both of simple substances, remaining merely in their own form, and of compositions, as of hard sealing-wax, & of certain other mixtures besides, made of unctuous stuffs. We must, however, investigate more fully whence that tendency arises, and what those forces be, concerning which a few men have brought forward very little, the crowd of philosophizers nothing at all. By Galen three kinds of attractives in general were recognized in nature: a First class of those substances which attract by their elemental quality, namely, heat; the Second is the class of those which attract by the succession of a vacuum; the Third is the class of those which attract by a property of their whole substance, which are also quoted by Avicenna and others. These classes, however, cannot in any way satisfy us; they neither embrace the causes of amber, jet, and diamond, and of other similar substances (which derive their forces on account of the same virtue); nor of the loadstone, and of all magnetick substances, which obtain their virtue by a very dissimilar and alien influence from them, derived from other sources. Wherefore also it is fitting that we find other causes of the motions, or else we must wander (as in darkness), with these men, and in no way reach the goal. Amber truly does not allure by heat, since if warmed by fire and brought near straws, it does not attract them, whether it be tepid, or hot, or glowing, or even when forced into the flame. Cardan (as also Pictorio) reckons that this happens in no different way129 than with the cupping-glass, by the force of fire. Yet the attracting force of the cupping-glass does not really come from the force of fire. But he had previously said that the dry substance wished to imbibe fatty humour, and therefore it was borne towards it. But these statements are at variance with one another, and also foreign to reason. For if amber had moved towards its food, or if other bodies had inclined towards amber as towards provender, there would have been a diminution of the one which was devoured, just as there would have been a growth of the other which was sated. Then why should an attractive force of fire be looked for in amber? If the attraction existed from heat, why should not very many other bodies also attract, if warmed by fire, by the sun, or by friction? Neither can the attraction be on account of the dissipating of the air, when it takes place in open air (yet Lucretius the poet adduces this as the reason for magnetical motions). Nor in the cupping-glass can heat or fire attract by feeding on air: in the cupping-glass air, having been exhausted into flame, when it condenses again and is forced into a narrow space, makes the skin and flesh rise in avoiding a vacuum. In the open air warm things cannot attract, not metals even or stones, if they should be strongly incandescent by fire. For a rod of glowing iron, or a flame, or a candle, or a blazing torch, or a live coal, when they are brought near to straws, or to a versorium, do not attract; yet at the same time they manifestly call in the air in succession; because they consume it, as lamps do oil. But concerning heat, how it is reckoned by the crowd of philosophizers, in natural philosophy and in materia medica to exert an attraction otherwise than nature allows, to which true attractions are falsely imputed, we will discuss more at length elsewhere, when we shall determine what are the properties of heat and cold. They are very general qualities or kinships of a substance, and yet are not to be assigned as true causes, and, if I may say so, those philosophizers utter some resounding words; but about the thing itself prove nothing in particular. Nor does this attraction accredited to amber arise from any singular quality of the substance or kinship, since by more thorough research we find the same effect in very many other bodies; and all bodies, moreover, of whatever quality, are allured by all those bodies. Similarity also is not the cause; because all things around us placed on this globe of the earth, similar and dissimilar, are allured by amber and bodies of this kind; and on that account no cogent analogy is to be drawn either from similarity or identity of substance. But neither do similars mutually attract one another, as stone stone, flesh flesh, nor aught else outside the class of magneticks and electricks. Fracastorio would have it that "things which mutually attract one another are similars, as being of the same species, either in action or in right subjection. Right subjection is that from which is emitted the emanation which attracts and which in mixtures often lies hidden on account of their lack of form, by reason of which they are often different in act from what they are in potency. Hence it may be that hairs and twigs move towards amber and towards diamond, not because they are hairs, but because either there is shut up in them air or some other principle, which is attracted in the first place, and which bears some relation and analogy to that which attracts of itself; in which diamond and amber agree through a principle common to each." Thus far Fracastorio. Who if he had observed by a large number of experiments that all bodies are drawn to electricks except those which are aglow and aflame, and highly rarefied, would never have given a thought to such things. It is easy for men of acute intellect, apart from experiments and practice, to slip and err. In greater error do they remain sunk who maintain these same substances to be not similar, but to be substances near akin; and hold that on that account a thing moves towards another, its like, by which it is brought to more perfection. But these are ill-considered views; for towards all electricks all things move130 except such as are aflame or are too highly rarefied, as air, which is the universal effluvium of this globe and of the world. Vegetable substances draw moisture by which their shoots are rejoiced and grow; from analogy with that, however, Hippocrates, in his De Natura Hominis, Book I., wrongly concluded that the purging of morbid humour took place by the specifick force of the drug. Concerning the action and potency of purgatives we shall speak elsewhere. Wrongly also is attraction inferred in other effects; as in the case of a flagon full of water, when buried in a heap of wheat, although well stoppered, the moisture is drawn out; since this moisture is rather resolved into vapour by the emanation of the fermenting wheat, and the wheat imbibes the freed vapour. Nor do elephants' tusks attract moisture, but drive it into vapour or absorb it. Thus then very many things are said to attract, the reasons for whose energy must be sought from other causes. Amber in a fairly large mass allures, if it is polished; in a smaller mass or less pure it seems not to attract without friction. But very many electricks (as precious stones and some other substances) do not attract at all unless rubbed. On the other hand many gems, as well as other bodies, are polished, yet do not allure, and by no amount of friction are they aroused; thus the emerald, agate, carnelian, pearls, jasper, chalcedony, alabaster, porphyry, coral, the marbles, touchstone, flint, bloodstone, emery131, do not acquire any power; nor do bones, or ivory, or the hardest woods, as ebony, nor do cedar, juniper, or cypress; nor do metals, silver, gold, brass, iron, nor any loadstone, though many of them are finely polished and shine. But on the other hand there are some other polished substances of which we have spoken before, toward which, when they have been rubbed, bodies incline. This we shall understand only when we have more closely looked into the prime origin of bodies. It is plain to all, and all admit, that the mass of the earth, or rather the structure and crust of the earth, consists of a twofold material, namely, of fluid and humid matter, and of material of more consistency and dry. From this twofold nature or the more simple compacting of one, various substances take their rise among us, which originate in greater proportion now from the earthy, now from the aqueous nature. Those substances which have received their chief growth from moisture, whether aqueous or fatty, or have taken on their form by a simpler compacting from them, or have been compacted from these same materials in long ages, if they have a sufficiently firm hardness, if rubbed after they have been polished and when they remain bright with the friction — towards those substances everything, if presented to them in the air, turns, if its too heavy weight does not prevent it. For amber has been compacted of moisture, and jet also. Lucid gems are made of water; just as Crystal132, which has been concreted from clear water, not always by a very great cold, as some used to judge, and by very hard frost, but sometimes by a less severe one, the nature of the soil fashioning it, the humour or juices being shut up in definite cavities, in the way in which spars are produced in mines. So clear glass is fused out of sand, and from other substances, which have their origin in humid juices. But the dross of metals, as also metals, stones, rocks, woods, contain earth rather, or are mixed with a good deal of earth; and therefore they do not attract. Crystal, mica, glass, and all electricks do not attract if they are burnt or roasted; for their primordial supplies of moisture perish by heat, and are changed and exhaled. All things therefore which have sprung from a predominant moisture and are firmly concreted, and retain the appearance of spar and its resplendent nature in a firm and compact body, allure all bodies, whether humid or dry. Those, however, which partake of the true earth-substance or are very little different from it, are seen to attract also, but from a far different reason, and (so to say) magnetically; concerning these we intend to speak afterwards. But those substances which are more mixed of water and earth, and are produced by the equal degradation of each element (in which the magnetick force of the earth is deformed and remains buried; while the watery humour, being fouled by joining with a more plentiful supply of earth, has not concreted in itself but is mingled with earthy matter), can in no way of themselves attract or move from its place anything which they do not touch. On this account metals, marbles, flints, woods, herbs, flesh, and very many other things can neither allure nor solicit any body either magnetically or electrically. (For it pleases us to call that an electrick force, which hath its origin from the humour.) But substances consisting mostly of humour, and which are not very firmly compacted by nature (whereby do they neither bear rubbing, but either melt down and become soft, or are not levigable, such as pitch, the softer kinds of resin, camphor, galbanum, ammoniack133, storax, asafœtida, benzoin, asphaltum, especially in rather warm weather) towards them small bodies are not borne; for without rubbing most electricks do not emit their peculiar and native exhalation and effluvium. The resin turpentine when liquid does not attract; for it cannot be rubbed; but if it has hardened into a mastick it does attract. But now at length we must understand why small bodies turn towards those substances which have drawn their origin from water; by what force and with what hands (so to speak) electricks seize upon kindred natures. In all bodies in the world two causes or principles have been laid down, from which the bodies themselves were produced, matter and form134. Electrical motions become strong from matter, but magnetick from form chiefly; and they differ widely from one another and turn out unlike, since the one is ennobled by numerous virtues and is prepotent; the other is ignoble and of less potency, and mostly restrained, as it were, within certain barriers; and therefore that force must at times be aroused by attrition or friction, until it is at a dull heat and gives off an effluvium and a polish is induced on the body. For spent air, either blown out of the mouth or given off from moister air, chokes the virtue. If indeed either a sheet of paper or a piece of linen be interposed, there will be no movement. But a loadstone, without friction or heat, whether dry or suffused with moisture, as well in air as in water, invites magneticks, even with the most solid bodies interposed, even planks of wood or pretty thick slabs of stone or sheets of metal. A loadstone appeals to magneticks only; towards electricks all things move. A loadstone135 raises great weights; so that if there is a loadstone weighing two ounces and strong, it attracts half an ounce or a whole ounce. An electrical substance only attracts very small weights; as, for instance, a piece of amber of three ounces weight, when rubbed, scarce raises a fourth part of a grain of barley. But this attraction of amber and of electrical substances must be further investigated; and since there is this particular affection of matter, it may be asked why is amber rubbed, and what affection is produced by the rubbing, and what causes arise which make it lay hold on everything? As a result of friction it grows slightly warm and becomes smooth; two results which must often occur together. A large polished fragment of amber or jet attracts indeed, even without friction, but less strongly; but if it be brought gent............