As with the water-wheel, so its congener, the windmill, beloved of artists, is going. A motive power as cheap as water is the wind, but, unfortunately, it is not so reliable. It is believed that the Chinese were the first to use the wind as a motive power for mills, and we have no record as to when they were introduced into Europe; we only know they were in use in the twelfth century. As a rule, in England, windmills have four arms, or ‘whips,’ but sometimes they104 have six. These arms are generally covered with strong canvas, but occasionally they are covered with thin boarding; they are set at an angle, which varies according to the fancy of the miller, but the shaft to which they are attached (called the ‘wind shaft’) is invariably placed at an inclination of 10 or 15 degrees, in order that the revolving arms should clear the bottom portion of the mill.

A Post Mill.

A Water-Wheel Mill.

The oldest kind of windmill is called a post mill, 105

106because the whole structure is centred on a post, or pivot, and, when the wind shifts, the mill has to be turned bodily to meet it, by means of a long lever. The smock, or frock, windmill is an improvement upon the post mill; the building itself is stationary and permanent, but the head or cap, where is the wind shaft, rotates, and this is more easily managed.

For hundreds of years people were contented with the four and six arms to their windmills, and it was only in modern times that Messrs. J. Warner and Sons, of Cripplegate, London, patented their annular sails, which, as is plain to the meanest capacity, are vastly superior. The shutters, or ‘vanes,’ are connected with spiral springs, which keep them up to the best angle of ‘weather, for light winds. If the strength of the wind increases, the vanes give to the wind, forcing back the springs, and thus the area on which the wind acts diminishes. In addition, there are a striking lever and tackle for setting the vanes edgeways to the wind, when the mill is stopped, or a storm expected.

We have seen how from the very first man used stones wherewith to triturate his corn, and to this day stones are still used for grinding, although their days are in all probability numbered, and in a very little time they, with the windmill, will be relegated to limbo. The Encyclop?dia Britannica gives such an excellent description of these mill-stones, that I quote it in its entirety.

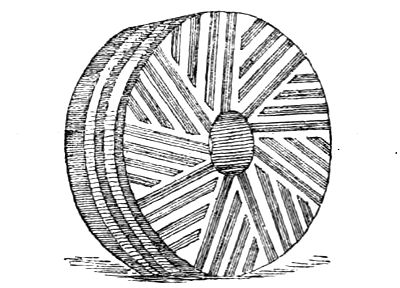

The Grinding Surface of a Millstone.

‘They consist of two flat cylindrical masses inclosed within a wooden or sheet metal case, the lower, or bed-stone, being permanently fixed, while the upper,107 or runner, is accurately pivoted and balanced over it The average size of millstones is about four feet two inches in diameter, by twelve inches in thickness, and they are made of a hard but cellular siliceous stone, called buhr-stone, the best qualities of which are obtained from La-Ferté-sous-Jouarre, department of Seine et Marne, France. Millstones are generally built up of segments, bound together round the circumference by an iron hoop, and backed with plaster of Paris. The bed-stone is dressed to a perfectly flat plane surface, and a series of grooves, or shallow depressions, are cut in it, generally in the manner shown, which represents the grinding surface of an upper or running stone. The grooves on both are made to correspond exactly, so that when the one is rotated over the other the sharp edges of the grooves,108 meeting each other, operate like a rough pair of scissors, and thus the effect of the stones on grain submitted to their action is at once that of cutting, squeezing, and crushing. The dressing and grooving of millstones is generally done by hand picking, but sometimes black amorphous diamonds (carbonado) are used, and emery wheel dressers have likewise been suggested. The upper stone, or runner, is set in motion by a spindle on which it is mounted, which passes up through the centre of the bed-stone, and there are screws and other appliances for adjusting and balancing the stone. Further provision is made within the stone case for passing through air to prevent too high a heat being developed in the grinding operation, and sweepers for conveying the flour to the meal spout are also provided.

‘The ground meal delivered by the spout is carried forward in a conveyor, or creeper box, by means of an Archimedean screw, to the elevators, by which it is lifted to an upper floor to the bolting or flour-dressing machine. The form in which this apparatus was formerly employed consisted of a cylinder mounted on an inclined plane, and covered externally with wire cloth of different degrees of fineness, the finest being at the upper part of the cylinder, where the meal is admitted. Within the cylinder, which was stationary, a circular brush revolved, by which the meal was pressed against the wire cloth, and, at the same time, carried gradually towards the lower extremity, sifting out, as it proceeded, the mill products into different grades of fineness, and finally delivering the coarse bran at the extremity of the109 cylinder. For the operation of bolting or dressing, hexagonal or octagonal cylinders, about three feet in diameter, and from 20 to 25 feet long, are now commonly employed. These are mounted horizontally on a spindle for revolving, and externally they are covered with silk of different degrees of fineness, whence they are called “silks,” or “silk dressers.” Radiating arms or other devices for carrying the meal gradually forward as the apparatus revolved, are fixed within the cylinders; and there is also an arrangement of beaters, which gives the segments of cloth a sharp tap, and thereby facilitates the sifting action of the apparatus. Like all other mill machines, the modifications of the silk dresser are numerous,’

We have seen the ordinary operation of grindin............